Money

The Convergence of Money: One Wallet to Rule Shopping, Saving, and Investing

This chapter explores how money could incorporate sustainability as a feature.

“Money is information… it shouldn’t be more expensive or slower than sending an email.” (K. Käärmann, Co-Founder of the Wise , formerly known as Transferwise, money transfer platform), said in 2018 (Käärmann, 2018)

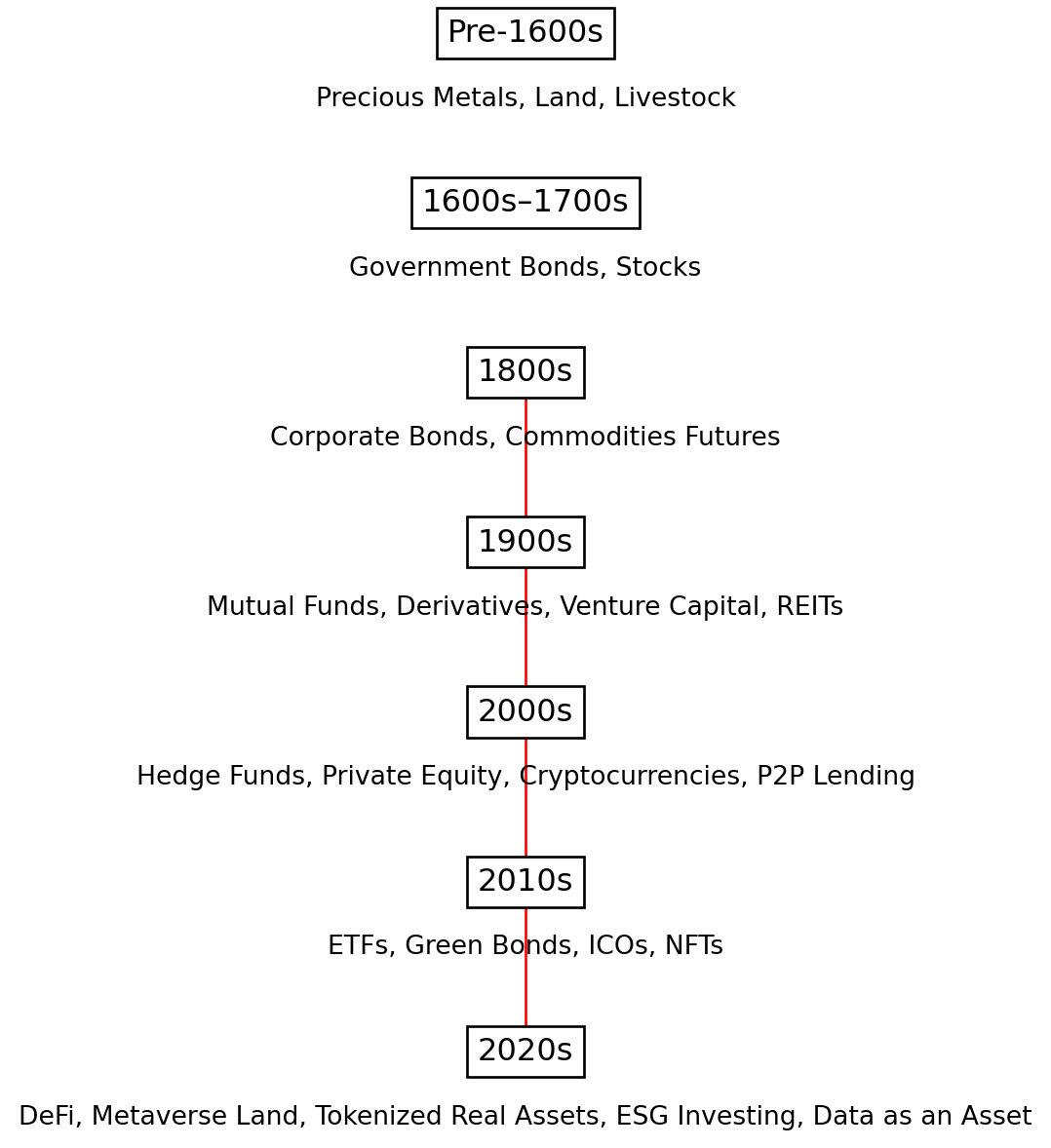

Money itself is changing and the meaning of money is becoming more diverse. Traditionally, money referred to the fiat money created by governments by law, using central banks, which loan money to commercial banks, that in turn make it available to the society. Now, we also have new types of money created by companies and individuals using blockchain-cryptography based distributed databases, which keep track of transactions (who-paid-whom). We have various types of tokens of value, such as cryptocurrencies, digital assets, loyalty points, etc, which can all function as types of money. Whatever the method of creation, in essence, money is a system of trust where something is used as a medium of value exchange and accepted by other people as payment.

Spurred by Fintech: The Democratization of Finance: A Precursor for Sustainable Superapps

Digital money in its various forms connects industries on popular financial mobile apps, which makes digital money more accessible and socially engaging, appealing to people who are active online. Because of the democratization of finance enabled by digitization and financial technologies, the journey from consumer to investor is becoming increasingly simple. Consumer-oriented financial apps increasingly enable new user interactions which blur boundaries between shopping, saving, and investing - termed here “money convergence”. Empowering consumers to access finance through digital technologies and delivering a simple user experience is the fintech trend of the last decade. Motivated by boosting user numbers, apps such as N26 and Revolut, that started out with only payments-focused businesses, founded in 2013 and 2015, respectively, began making efforts to expand into all-in-one financial superapps offering varied saving and investing services (Kickstart Your Investment Journey, 2023; Revolut Launches ETF Trading Platform in Europe, 2023).

While it took N26 and Revolut more than a decade to grow into global businesses, fintechs can growth really fast. Just last year in Canada, Neo Financial, which offers a mobile app and credit cards to consumers featuring cashback rewards on payments, savings and investing, won Canada’s fastest growing company award in 2024, posting a 3-year revenue growth of 38,431%, earning between $75M and $100M USD in annual revenue from 1.3 million customers (“Ranking Canada’s Top Growing Companies of 2024,” 2024). (Qorus, 2023) a survey of 200 banking executives worldwide, revealed we’re in a digital banking revolution, with growing adoption of personalization, automation, and embedded finance - the availability of savings, loans, insurance, debit cards, and investment opportunities embedded within the apps of non-financial platforms, like e-commerce or social media platforms.

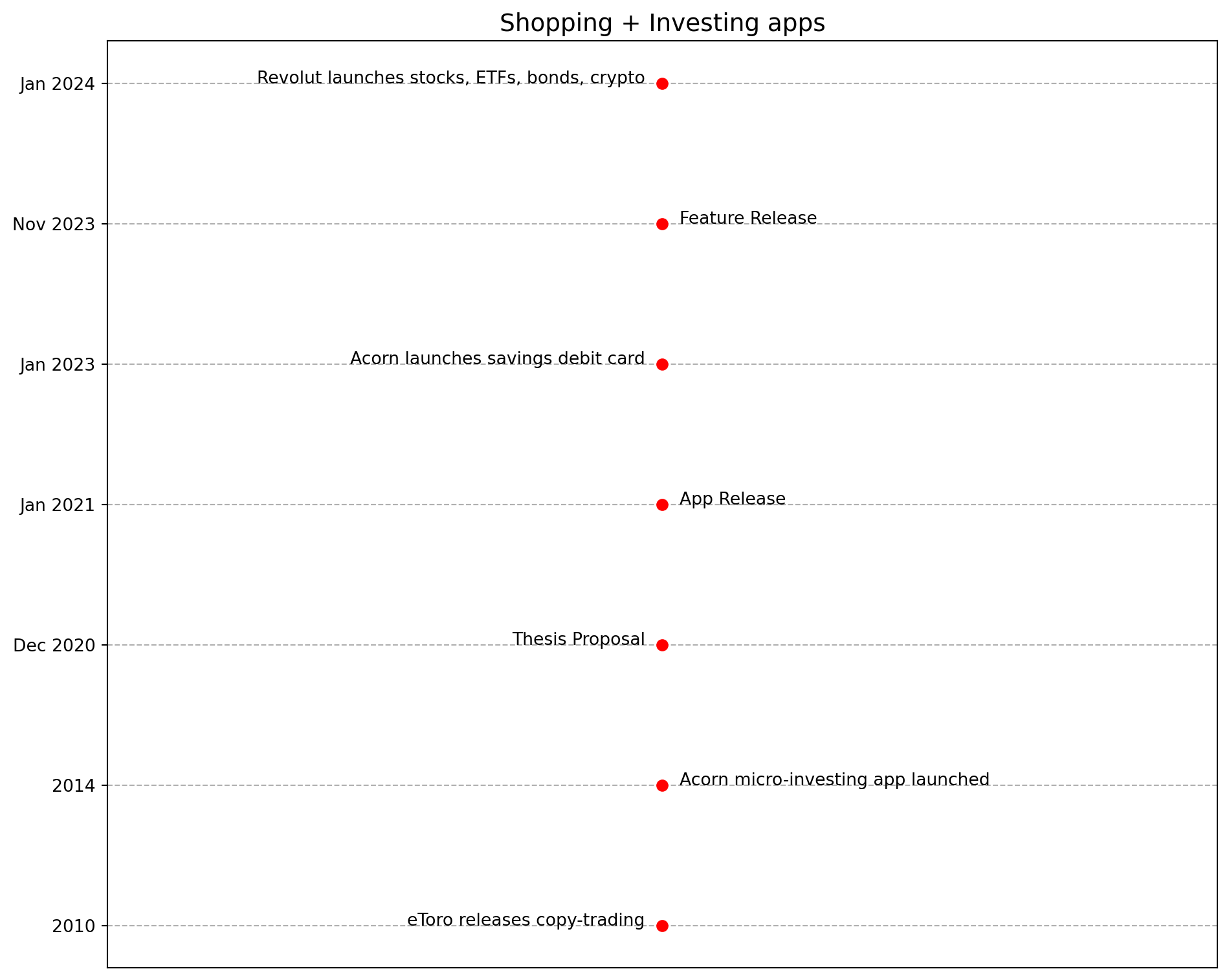

Figure 1: Fintech Growth

Financial Literacy and Education: Young Investors Follow Financial Influencers

Young investors are typically retail investors, investing small amounts of money for themselves. (Unless they have inherited wealth or are among the very few who work in institutions such as investment firms, university endowments, pension funds or mutual funds, and have a say in where to invest large amounts of other peoples’ money.) Retail investors face many challenges in comparison with their institutional counterparts. For instance, they may have much less time to do proper research, face information asymmetries, where finding good information is limited by time, ability, as well as financial literacy, whereas professional investors have the tools, skills, time, and knowledge, to make better investment decisions.

The common expectation is that young investors typically have less understanding financial concepts. While consumers are beginning to become more money-savvy, they still lag in both financial and sustainability literacy. Financial and sustainability literacy are intertwined. Integrating these literacies is essential, because a financially informed public is better equipped to channel capital toward environmentally beneficial uses. Media plays a significant role here, with retail investing being heavily influenced by social media influencers.

Popular financial blogger (Austin Ryder, 2020) believes a good starting point is to ask the user to define their financial habits: are you consumer or investor? This helps users recognize whether their spending habits define them primarily as consumers or as investors. (SmartWealth, 2021) urges readers to “consume knowledge, not products”: for financial health one should get rid of debt, automate tracking of expenses and savings, and create a pathway for income to flow into investments; consumer mindset is the main obstacle that keeps people from financial independence and investing. Investing can intersect with gender and race, as for example, during COVID-19, the financial advisor Malaika Maphalala co-led the “Invest in Black Economic Liberation” calling for racial justice investing to direct flows into sustainable funds (naturalinvest, 2020). On TikTok, (lizlivingblue, n.d.) promotes the IMPACT investing app by Interactive Brokers which is a mobile trading platform focused on socially conscious investors interested in sustainability (Trahant, 2022).

| Feature | IMPACT by Interactive Brokers | Lightyear | Revolut |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Audience | Sustainability-focused investors; value-driven alignment | European retail investors | Everyday users with casual interest in investing |

| Investment Products | Stocks, ETFs, mutual funds, options, bonds, fractional shares | Stocks, ETFs, multi-currency accounts | US & EU stocks, crypto, commodities, fractional shares |

| Sustainability Focus | Strong. Core to the app. Lets users filter companies by ESG values and track portfolio impact. | None. Focuses on transparency and low fees | Minimal. Some ESG ETFs; no impact tracking or custom filters |

| Fees | Very low (starting at $0 commissions, with some market/data fees) | Low, with no account fee; FX markup 0.35% outside base currency | Free plan has high spreads; paid tiers offer lower fees; several FX and withdrawal limits apply |

| Currency Conversion (FX) | Interbank FX rates; low spreads | 0.35% FX fee | Free plan: 1% FX fee; better rates in Premium accounts |

| Fractional Shares | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tax Documents | Yes, detailed reports | Yes, supports Estonian tax system | Limited; may need to do manual tracking for taxes |

| Mobile App Experience | Professional, ESG-focused UI | Clean, simple, intuitive | Gamified, casual, integrated with other Revolut services |

| Extra Features | Voting rights, ethical filters, carbon impact metrics | Interest on cash (like a bank account); multi-currency accounts | Cashback, budgeting, crypto, P2P payments, travel perks |

The next step is to provide frictionless digital pathways that let everyday purchases morph into micro-investments with transparent sustainability impacts. This user journey is a type of blended learning-by-doing experience. Framing the problem as a dual journey: first, helping users recognize whether their spending habits define them primarily as consumers or as investors, then giving users exposure to investment opportunities through familiar activities like shopping may hold the potential to boost financial literacy levels, enticing consumers to learn more about taking advantage of their financial opportunities as well as understanding how to manage the types or risk involved. Indeed, retail investor are the most vulnerable to misinformation and speculative hype if educational scaffolding is absent.

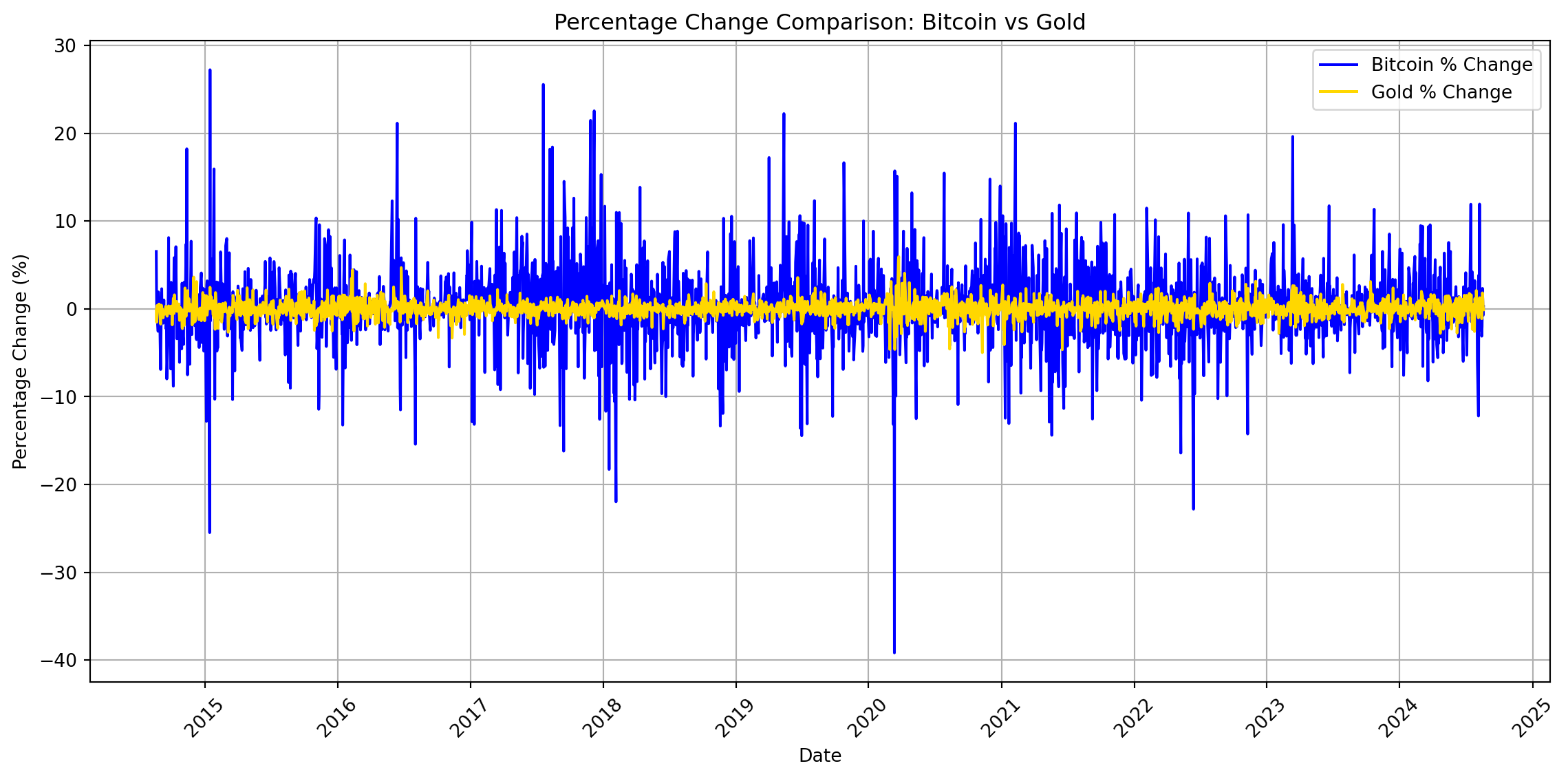

Financial superapps for shopping, saving, and investing are converging on digital platforms, aiming to permeate our daily financial lives, with features such banking, payments, transfers, rewards and cashback programs (e.g. Rakuten), automated micro-investing round-up to next dollar (e.g. Acorn, Stash, Swedbank, many others), retail investing (Robinhood, Public, Lightyear), copy-trading (eToro) and offering various investment vehicles, to name just a few: (fractional shares of) stocks, derivatives like CFDs and futures, microloans (Kiva), commodities and precious metals such as gold and silver (Revolut), physical assets such as real estate, land, forest and digital assets such as cryptocurrencies, NFTs, and many other alternative assets of varied price, volatility, liquidity, and risk profile.

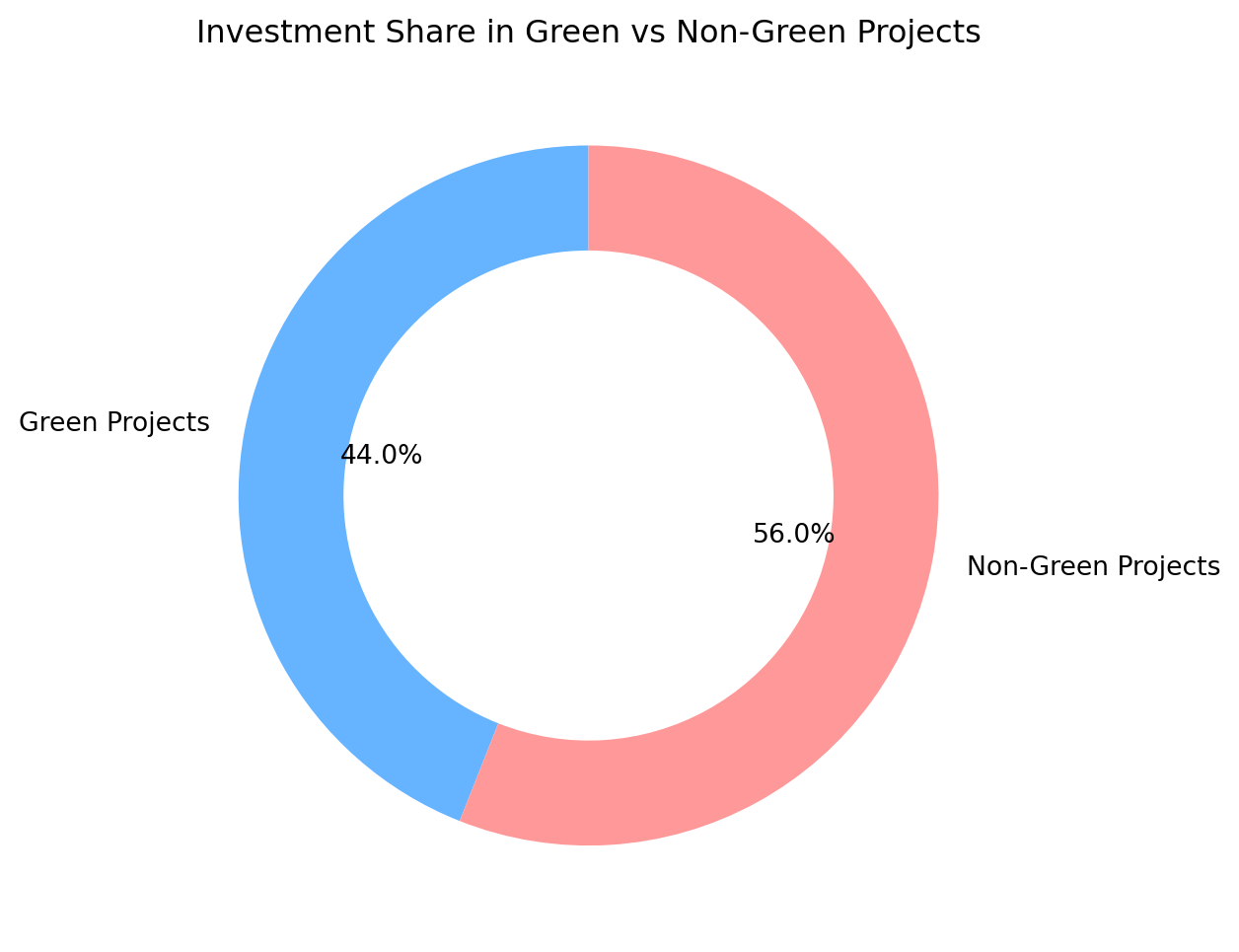

Figure 2: Green Retail vs Non-Green Retail

Community-based copy-trading apps live on the intersection of social media and investing, enabling financial inclusion through letting novice, inexperienced investors piggy-back on more sophisticated investors by copying their investments. In some ways community-investing competes with robo-advisors as communities can be led by professional investors and followed by less sophisticated investors. Because of this investing leadership aspect, investor communities can have the type of social proof, which robo-advisor do not possess. eToro’s, Robinhood’s and Dub’s copy trade feature turn portfolios, watch-lists and trade votes into public content (dub, 2025). The visible social proof approach can feel safer than robo-adviser; retail investors cite seeing what others do an important trust trigger (Andraszewicz et al., 2023).

Evidence of a similar phenomenon of peer behavior measurably shifting sustainability choices has been documented in the enterprise sector in green financing of Chinese industries, albeit in a modest 1–2% increase (incremental nudges); companies tend to invest green when they see when other companies signal a green preference (Yang et al., 2022). In a Swedish study, investors’ belief in sustainable investing was found to be affected by other investors: an online coordination game with 559 private investors showed that 2nd-order pro-sustainable beliefs (what one thinks others care about) also drove up sustainable asset allocations, underlining the social dimension of ESG investing (Luz et al., 2024).

Independent of what is the technology used, access to investing is about financial empowerment. Ugandan investor John Ssenkeezi celebrated on X (formerly known as Twitter) being able to vote at Apple’s 2022 AGM stockholder meeting using stock investments app Chipper Cash, which allows users by fractional‑shares, illustrating shareholder democracy for emerging‑market users (John Ssenkeezi, 2022). AngelList was an early pioneer in opening startup deal flow to retail users, offering access once reserved for angel investors and VCs. Similarly, community-based investment clubs could potentially enable everyday investors to pool resources and back sustainability initiatives alongside more experienced professionals.

Build a community can be lucrative. In Singapore, Chinese influencer Yuqing “Irene” Zhao’s photos generated S$7.5 million in 10 days as NFT sales; she tokenized her selfies as non-fungible tokens (NFTs) via IreneDAO, a decentralized version of OnlyFans, Discord, Twitch and Patreon, arguing that Web3 empowers creators to earn directly from their communities, turning fans into investors and aligning content creation with tokenized membership rights — evidence that retail capital can flow directly to media personalities through crypto communities (Irene Zhao, 2022; Yuqing Zhao, 2021). Similarly, in South Korea, media personalities have become “investable,” through more traditional financial vehicles, such as K-pop idols as the focus for “thematic” ETFs, including KPOP and Korean Entertainment ETF and the Mirae Asset Global X K-pop and Culture ETF, enabling fans and investors to financially participate in the growth of the Korean entertainment and celebrity-driven cultural capital (Darwyne, 2025).

Communities can be directed towards sustainability, by attracting people of a similar mindset. For example, minimalism is a movement of people living a simpler life; this probably always going to be a small percentage of people, yet a growing life-style choice. According to one study, consumers choose to engage in becoming minimalist in a non-linear process with overlapping stages (Oliveira De Mendonça et al., 2021). Yet, (Costa, 2018) Finnish socialists promote minimalism as part of their mainstream policies. In Tokyo, a YouTuber shares their life and the choices they made (Tokyo Simple Eco Life, 2021). Zero Waste Lifestyle is the opposite of overconsumption. Zero Waste suggests people buy in bulk for more savings and to reduce packaging. Through group purchases and community investing while also reducing consumption. Zero Waste municipality in Treviso is a whole region with a focus on living green. While Minimalism and Zero Waste need an ongoing effort, joining a one-day sustainability event is accessible for most people. Started in Estonia, the World Cleanup Day movement has attracted tens of millions of people to do beach and forest cleanups, all over the world.

Building a community is a way to design a context, where the culture creates certain expectations of behavior. Humans working together are able to achieve more than single individuals. “Any community on the internet should be able to come together, with capital, and work towards any shared vision. […] In the long term this moves to internet communities taking on societal endeavors.” (Panzarino, 2020). (Armstrong & Staff, 2021) believes leveraging different personalities and viewpoints can build more sustainable cultures; the focus on group consciousness suggests community-based sustainability action may be effective, when building a culture of sustainability, such as the garbage trucks in Taiwan. A communal event is a key building block for a thriving community, which can be directly experienced instead of just reading about it or watching a video.

New Rules of Money: Legislative Efforts Empowering Consumers to Deploy Capital in Sustainability

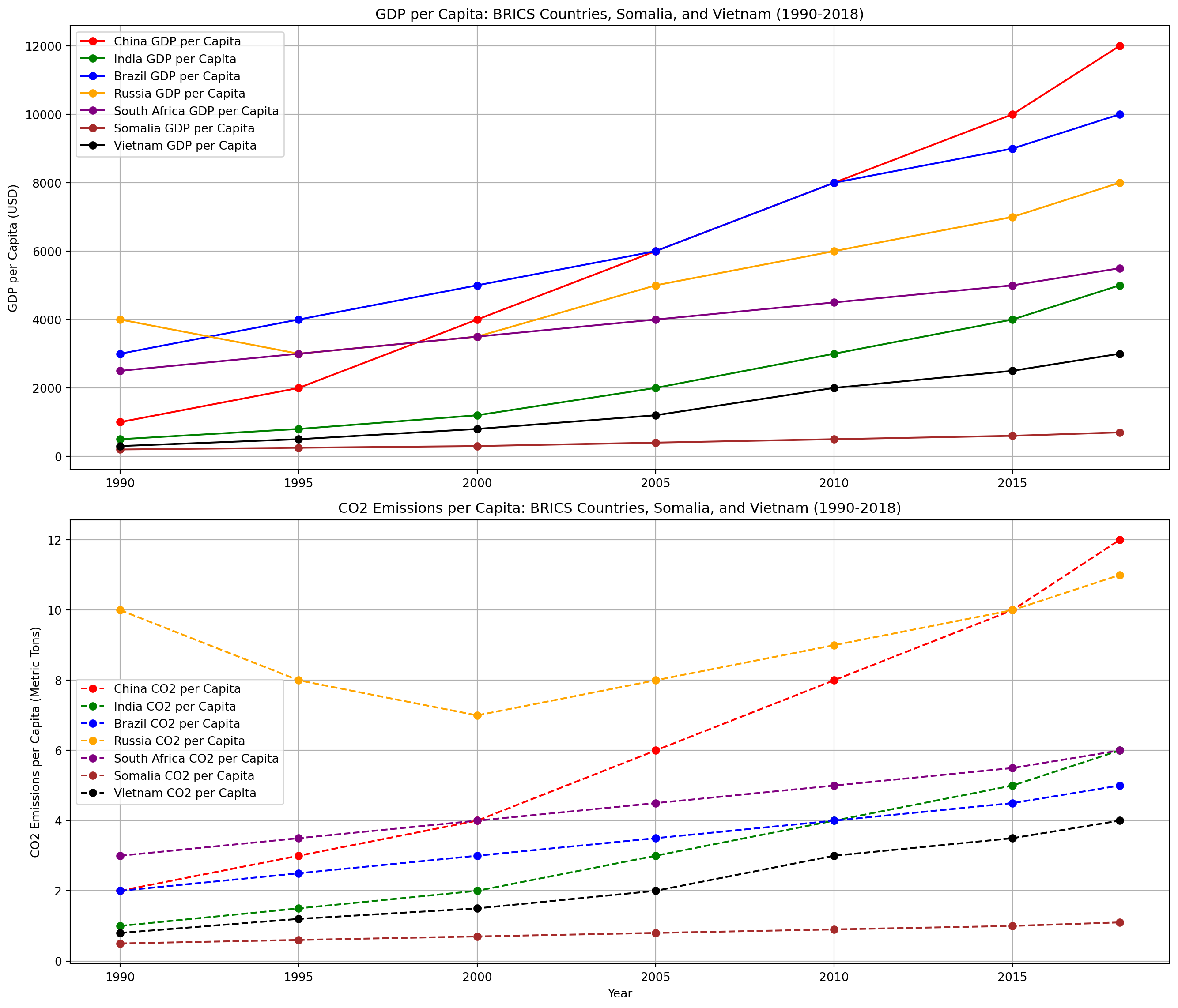

Regardless if it’s money spent on shopping or money saved and invested, these are all consumers’ financial decisions of capital allocation. In one way or another, people are giving their money to companies. The critical question is: do people choose to support sustainability-focused companies - companies which invest deeply into green innovation and eco-friendly practices - or do people choose companies that pay less attention to sustainability? While all financial transactions support economic growth in the sense of being reflected in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), not all money flows equally support sustainable economic growth.

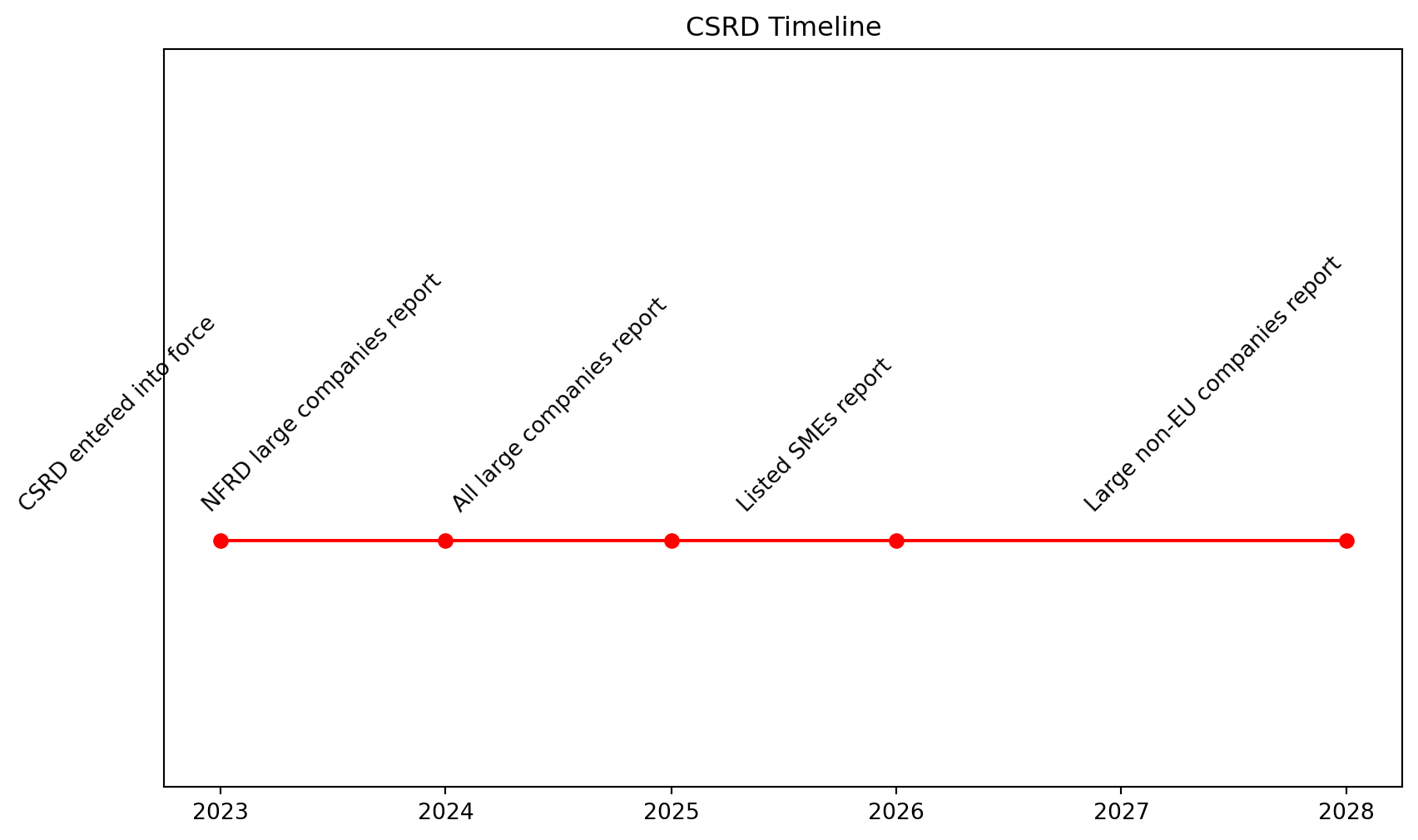

Legislation is catching up with fintechs and setting higher standards for consumer protection. For example the Directive 14 2014/65/EU, 2014 of The European Union fully recognizes the changing financial landscape trending towards the democratization of investments: “more investors have become active in the financial markets and are offered an even more complex wide-ranging set of services and instruments” (European Parliament, 2014). Some key legislation for investors has been put in place recently, for example “MiFID II is a legislative framework instituted by the European Union (EU) to regulate financial markets in the bloc and improve protections for investors” (Kenton, 2020). MiFID II and MiFIR will ensure fairer, safer and more efficient markets and facilitate greater transparency for all participants (European Securities and Markets Authority, 2017).

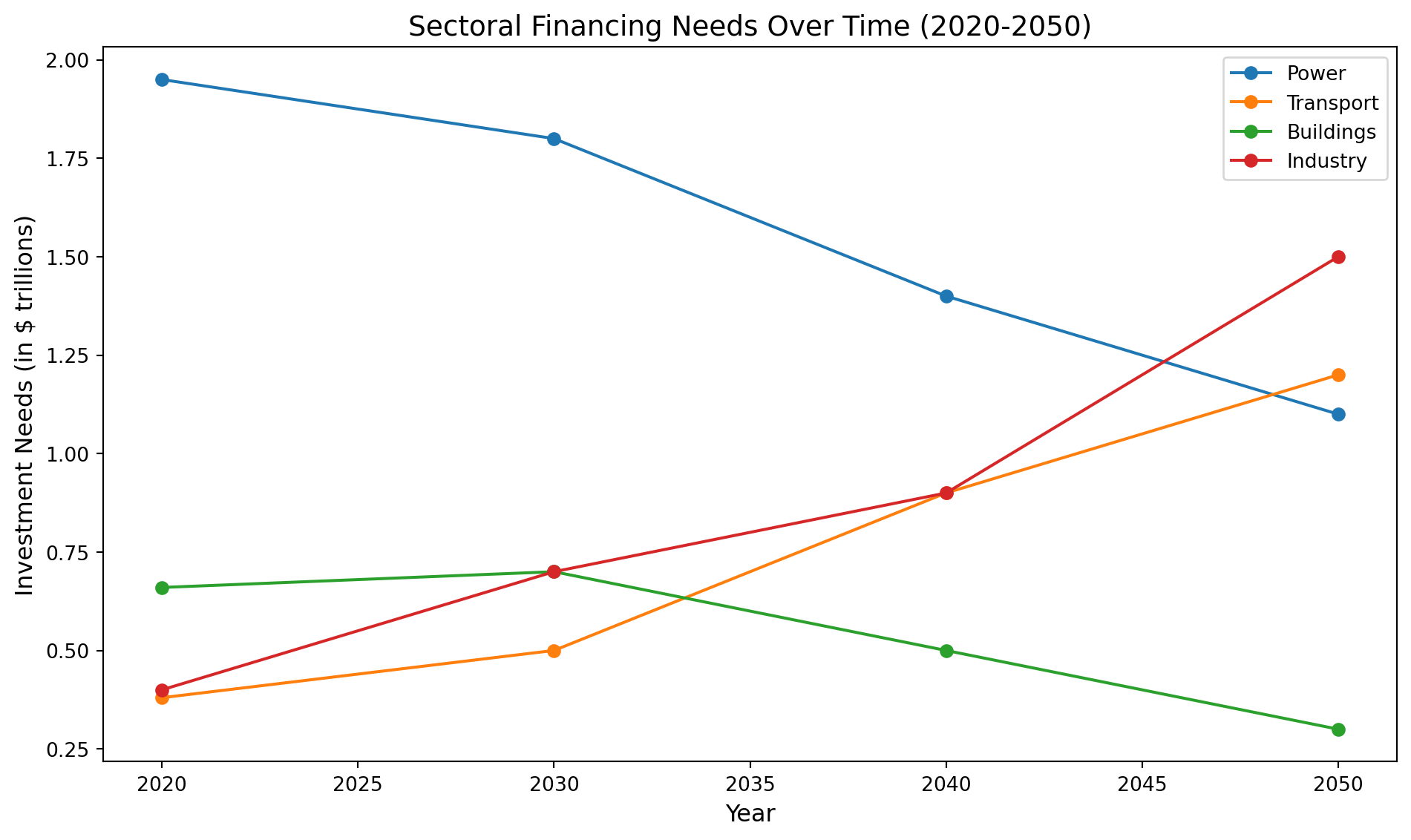

(PWC, 2020) Changes to laws and regulations aimed at achieving climate change mitigation is a key driver behind the wave of ESG adoption. The goal of these laws, first adopted in the European Union, a self-proclaimed leader in eco-friendliness, is to pressure unsustainable companies to change towards greener practices, in fear of losing their access to future capital, and to create a mechanism forcing entire environmentally non-compliant business sectors to innovate towards sustainability unless they want to suffer from financial penalties. On the flip side of this stick and carrot fiscal strategy, ESG-compliant companies will have incentives to access to cheaper capital and larger investor demand from ESG-friendly investors.

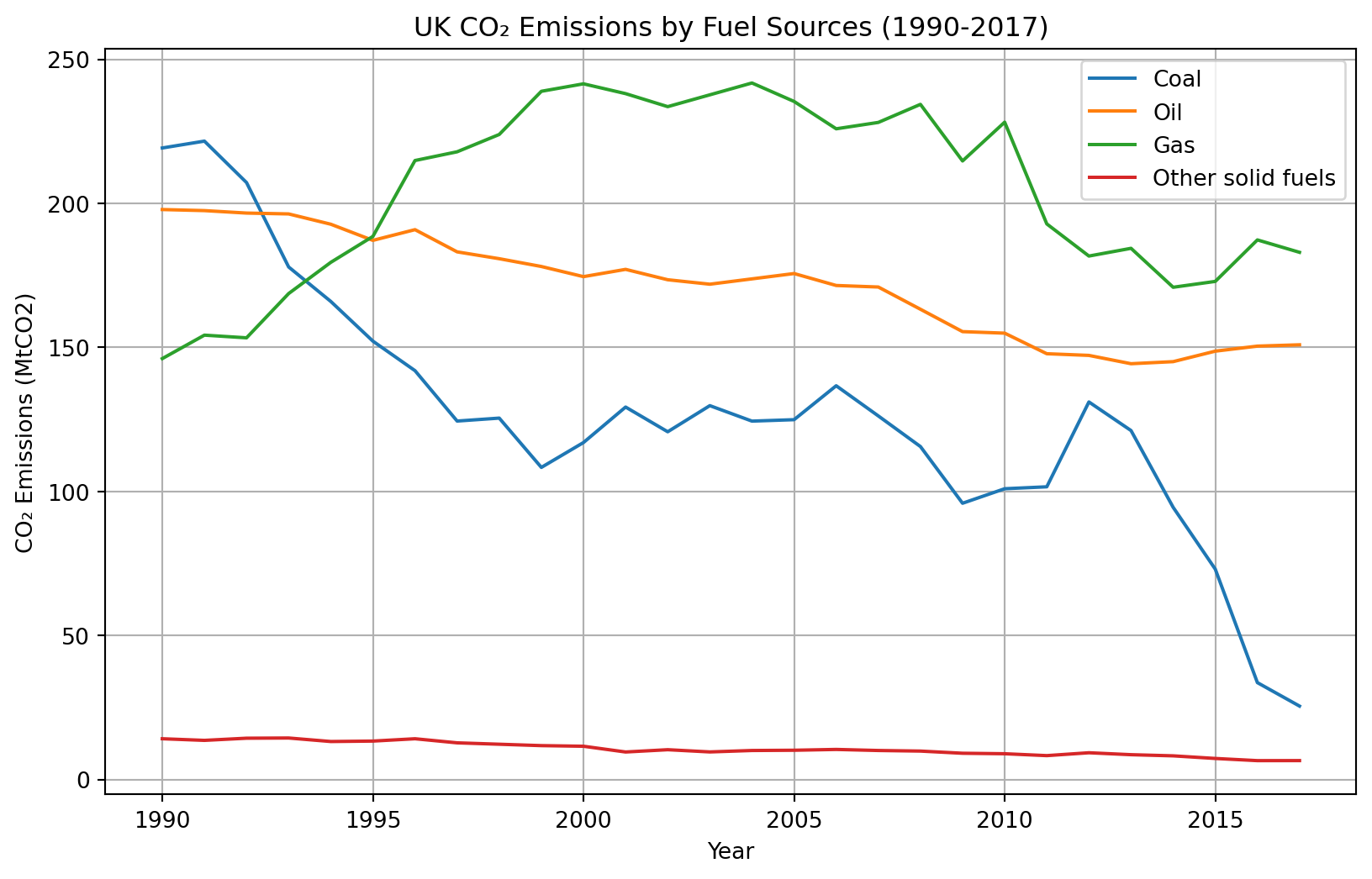

Already in 2001, while still part of the EU, the UK government was discussing ways to promote sustainable investment “fundamental changes in VAT or corporation taxes could be used to promote greener consumption and investment” (House of Commons, 2002). More recently, (HM Treasury, 2020) released a taxonomy of sustainable activities in the UK.

While the above trend is for governments to adapt to and work towards their environmental climate commitments and public demand, the sovereign risk remains an issue. For example, in the U.S. the policies supported by President Donald Trump during his presidency ran counter to many sustainability recommendations, including those directed at the financial markets, helping legacy industries stay competitive for longer through subsidies, and lack of regulation, or even regulation supporting legacy technologies (Quinson, 2020).

Governments are powerful in passing legislation, with a strong positive or negative ESG impact, and people do have a voice. Among the many grassroots campaigns, one environmental success story is about success story, asking that EU shops can’t sell deforestation products, gathering over 100 thousand online signatures (WeMove Europe, 2022). Subsequently, legislation banning products contributing to deforestation was passed by the EU Parliament and Council in 2023 and came into effect in July 2024 (Abnett & Abnett, 2024; European Parliament, 2023).

ESG Crisis and Opportunity

Opaque Metrics and Lack of Standardization

ESG ratings have faced criticism for lack of standards and failing to account for the comprehensive impact a company is having. (Foley et al., 2024) notes how Coca Cola fails to account the supply chain water usage when reporting becoming “water neutral” and calls on companies to release more detailed information; major ESG ratings omit 90% of the company’s water footprint. (Gemma Woodward, 2022) Identifies fundamental problems in current ESG frameworks include (1) inconsistent data, and (2) superficial rating schemes, and calls for a complete overhaul to restore credibility in sustainable investing. (Margaryta Kirakosian & Angus Foote, 2022) argues that ESG needs standardization of methodologies as the disparity is one of the key hurdles in finding the right sustainable strategy. This is supported by econometric analysis, showing how inconsistent ESG scoring methodologies and greenwashing risk can predict the yields of green bonds, meaning scoring variance could materially affect bond pricing (Baldi & Pandimiglio, 2022). Likewise, The Carbon Tracker Initiative finds that companies in the highest-emitting sectors fail to explain how their greenhouse-gas outputs translate into financial risk, based on an analysis of corporate disclosures (Frances Schwartzkopff, 2022b).

Fortunately, there are some investment advisors rebuffing misleading ESG claims made by asset managers. Prominent investment research firm Morningstar conducted a forensic analysis of the industry, and re-classified 1/5 of the tracked funds (over 1200 in total) or over $1 trillion USD in total valuation, as non-ESG; Hortense Bioy, Morningstar’s Head of Sustainability Research, commented these funds don’t integrate ESG factors “in a determinative way for their investment selection” (Schwartzkopff & Kishan, 2022).

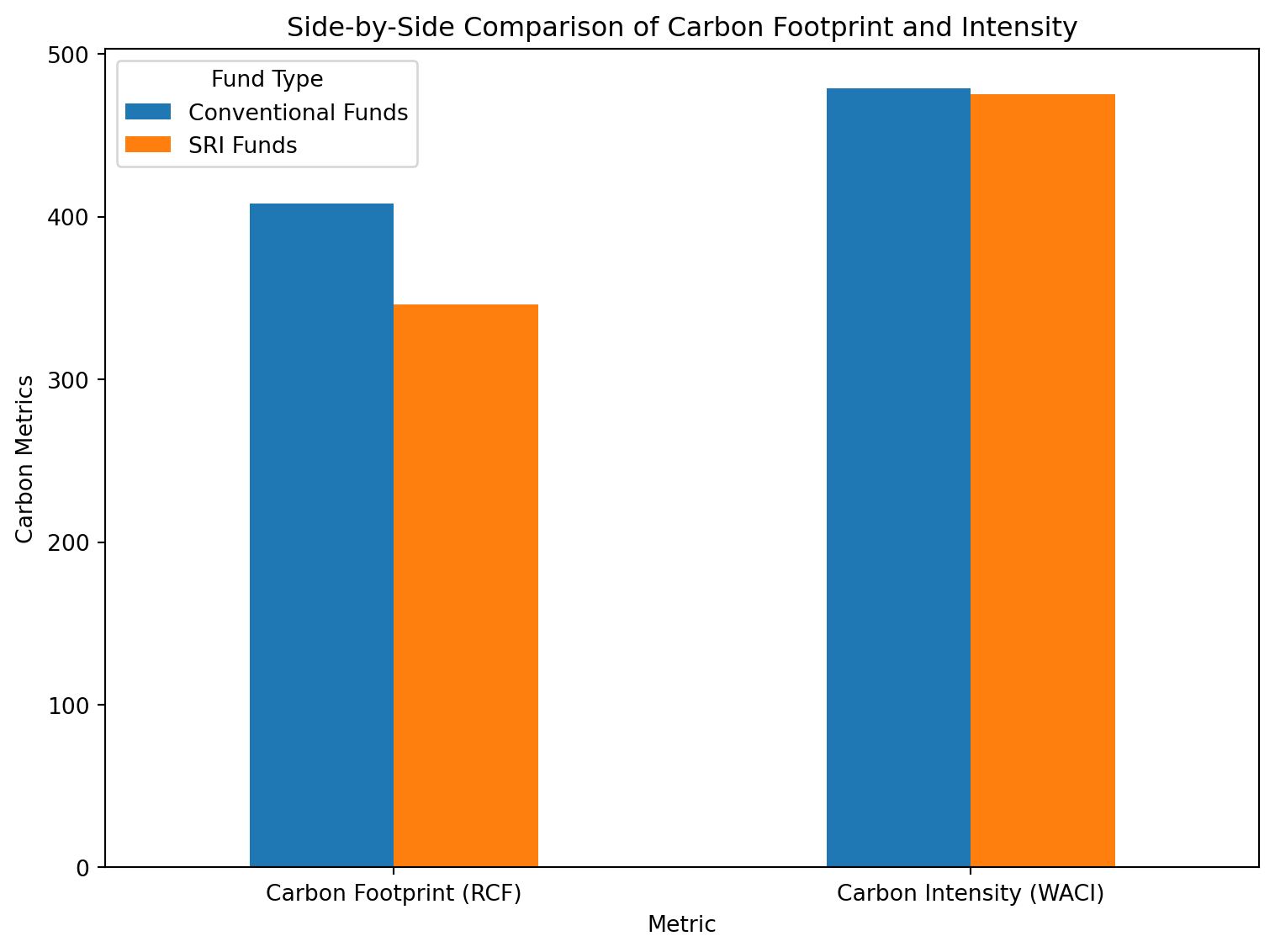

In theory, Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) integrates ESG criteria to screen out harmful industries and direct capital to companies with positive social and environmental impacts for both ethical and financial returns (Socially Responsible Investing Advisors, n.d.). Nonetheless, a large-scale input–output life-cycle assessment of 1340 European equity funds (11275 unique holdings) including sustainable (SRI) funds, and found that 24% of the sampled SRI funds actually show higher total CO2eq emissions exposure within their assets than a conventional market index (Popescu et al., 2023). (Amenc et al., 2023) reviewed ESG ratings from 3 major providers (Moody’s Analytics, MSCI Inc., and Refinitiv), finding that “well-rated companies do not emit significantly less carbon than those with lower scores”.

(ESG 浪潮反思:一間減碳表現優異、但產品有害健康的企業,符合 ESG 精神嗎?, 2022) critiques leading ESG rating methodologies (e.g., MSCI, Sustainalytics), showing they assess a company’s ability to withstand ESG-related financial risk (not its actual environmental, social, or governance performance), allowing firms like Philip Morris, which joined the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices (DJSI) in 2020 despite selling 7 trillion cigarettes per year, to score highly, and calls for urgent re-calibration of these frameworks.

The lack of rigor is creating a backlash against ESG reporting. (Yu, 2021) reports ESG is filled with greenwashing. (Anti-ESG Crusade in US Sweeps 15 States With More Laws in Works, 2023) several US states are introducing regulation for ESG to curb greenwashing. (Frances Schwartzkopff, 2022a) suggests the ESMA and EU has strengthened legislation to counter ESG greenwashing. (Shashwat Mohanty, 2022) “sustainable funds don’t buy Zomato’s ESG narrative”. (Bindman et al., 2024) reports large ESG funds managed by BlackRock and Vanguard are investing into JBS, a meat-packing company which is linked to deforestation of the Amazon rainforest through its supply chain.

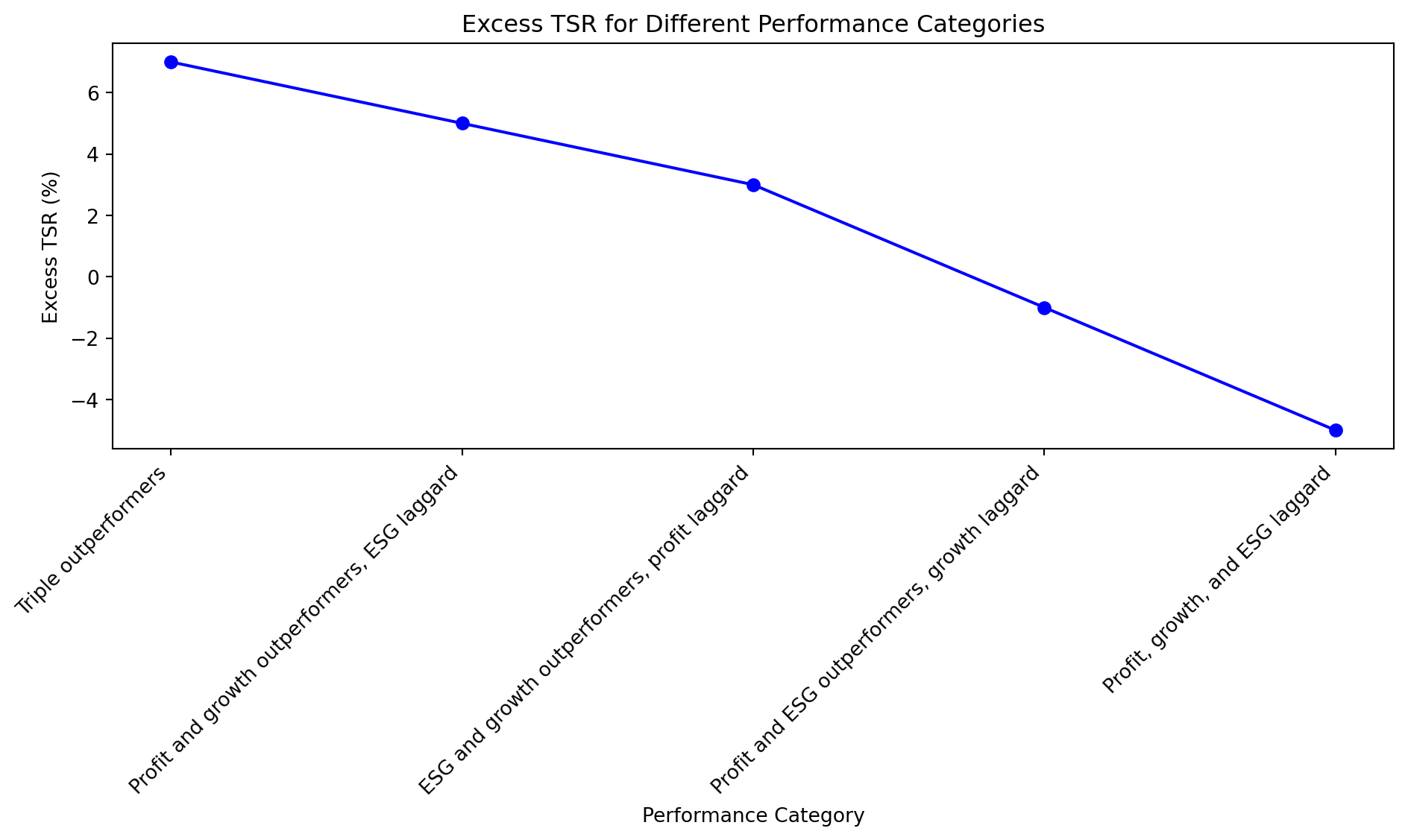

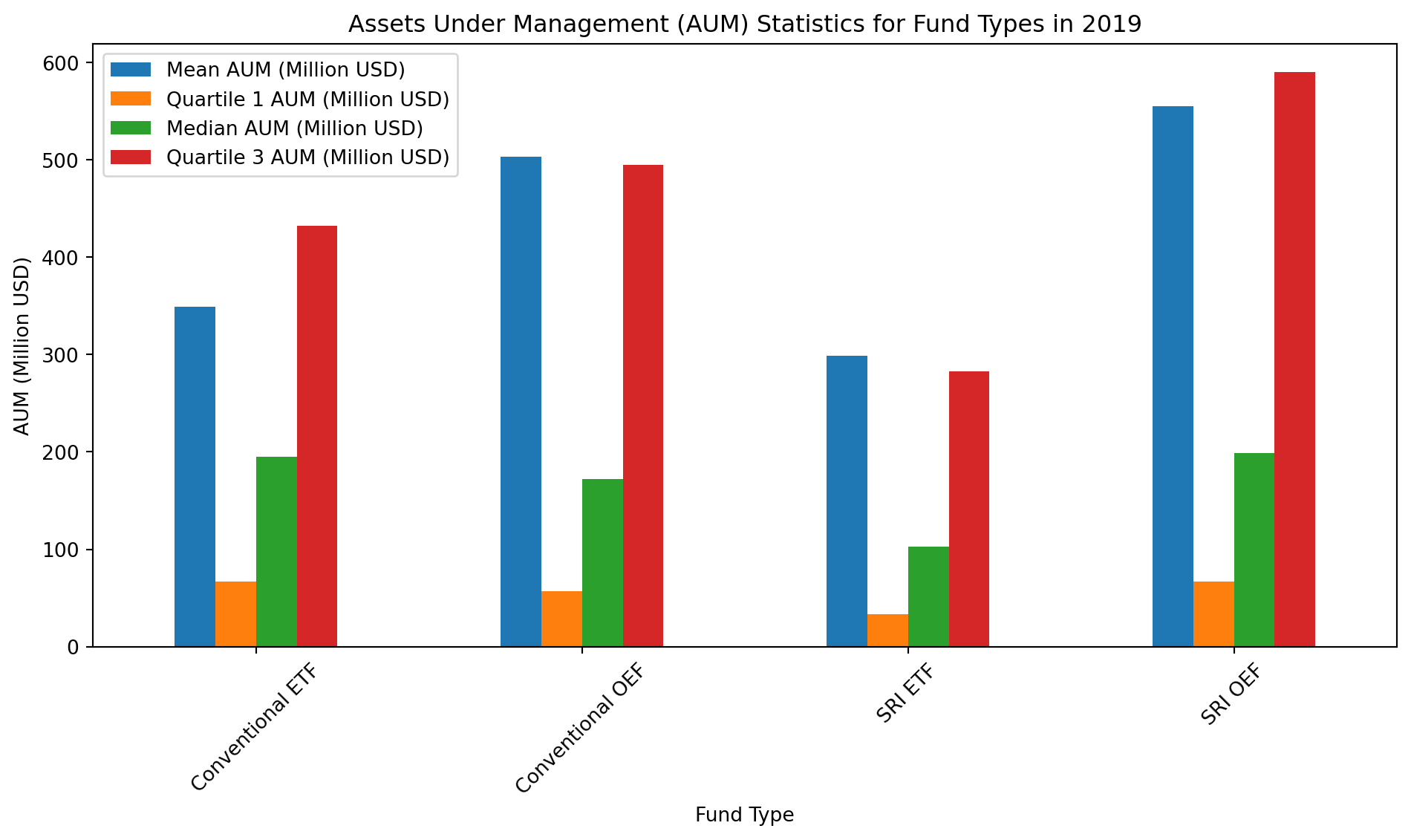

Figure 3: Conventional vs Socially Responsible Funds

(Sanjai Bhagat, 2022) argues that despite more than $2.7 trillion in ESG-rated AUM as of December 2021, (assets under management, the total market value of all the investments including stocks, bonds, crypto, etc.), that investment managers are looking after on behalf of their clients (81% in Europe and 13% in U.S.), funds marketed as ‘sustainable’ fail to deliver improvements to environmental and social metrics; the inconvenient truth is that ESG ratings don’t deliver better ESG performance. In the face a crisis of underperformance and mounting scandals, (James Phillipps, 2022) questions whether ESG is fundamentally broken or simply misunderstood. (PIETRO CECERE, 2023) calls ESG labeling confusing and arbitrary; fund selectors describe ESG labeling as “a total mess,” pointing to confusing definitions, inconsistent methodologies, and overlapping ratings that undermine clarity. (Financial Materiality Marks Next Big ESG Investing Battle, 2023) argues that the main challenge in credible ESG investing is defining which sustainability factors are genuinely financially material; the market is confused by inconsistent scoring methods and needs more government-backed policies that create incentives to align short- and long-term risk assessments. ESG-activist Georgia Elliott-Smith argues in her TEDx talk that large corporations are using ESG for greenwashing - but not changing their fundamental polluting practices (TEDx Talks, 2022).

ESG gave banks a new tool to market and sell environmentally conscious opportunities to institutional investors, for example: universities. A case in point being the partnership between HSBC and the University of Edinburgh (Reid, 2020). Some banks even use tactics such as co-branding with famous individuals. One of the largest private banks in Switzerland, Lombard Odier & Co (LOIM), launched a thematic bio-economy fund marketed using the words of The Prince of Wales, “Building a sustainable future is, in fact, the growth story of our time” (Kirakosian, Noveber 16, 2020). Investment can also be advertised in media publications. In the United Emirates, the richest oil-drilling region in the world, Mubadala, on of the state-owned sovereign wealth funds of the government of Abu Dhabi with $326 billion AUM, has taken out sponsored content in Bloomberg to market their national ESG vision and regulatory strategies to accelerate ESG investment growth toward net-zero goals, including many green energy projects; the Abu Dhabi funds together manage $1.7 trillion AUM (Maccioni, 2025; The Future of ESG Investing, n.d.).

Yet, the question remains, whether one can trust financial professional to hold ESG to a high standard. (Agnew, 2022) Argues that ESG has become a diluted corporate marketing label nearing the end of its usefulness, and urges a pivot toward more substantive responsible-investment practices beyond ticking the ESG checkbox. Banks are hiding emissions related to capital markets, which is a major financing source for oil and gas projects; the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) working group voted to attribute only 33% of CO2eq emissions from bond and equity underwriting to their own financed-emissions footprints, effectively excluding and hiding 2/3 of their carbon emissions (T. Wilkes, 2023). In the U.S., Blackrock, the largest private investment fund in the world with $10T USD under management, released guidance reflecting their plans to shift their investments to vehicles that are measured on ESG performance; however they later backtracked from their decision (Posner, 2024). In the U.K., while promising to become sustainable, oil companies are increasing production; Rishi Sunak, the Prime Minister of the UK at the time announced 100 new licenses for oil drilling (Noor, 2023). In a sense this strategy could be described as “have your cake and eat it too”, with investing going to all types of energy, regardless of its environmental footprint.

In early 2025, ESG investing saw $8.6 billion in global outflows, mainly due to political pushback in the U.S., including rollbacks of climate and DEI policies under the Trump administration. U.S. sustainable funds lost $6.1 billion, and Europe saw its first net outflow since 2018; ESG is shifting toward a more practical phase, with less focus on branding and more on measurable outcomes (Bioy, 2025; Johnson, 2025; Mitchell, 2025; Vosburg & Bioy, 2025).

Modern Slavery Persists and ESG Falls Short in Protecting Workers’ Rights and Mitigating Environmental Harm

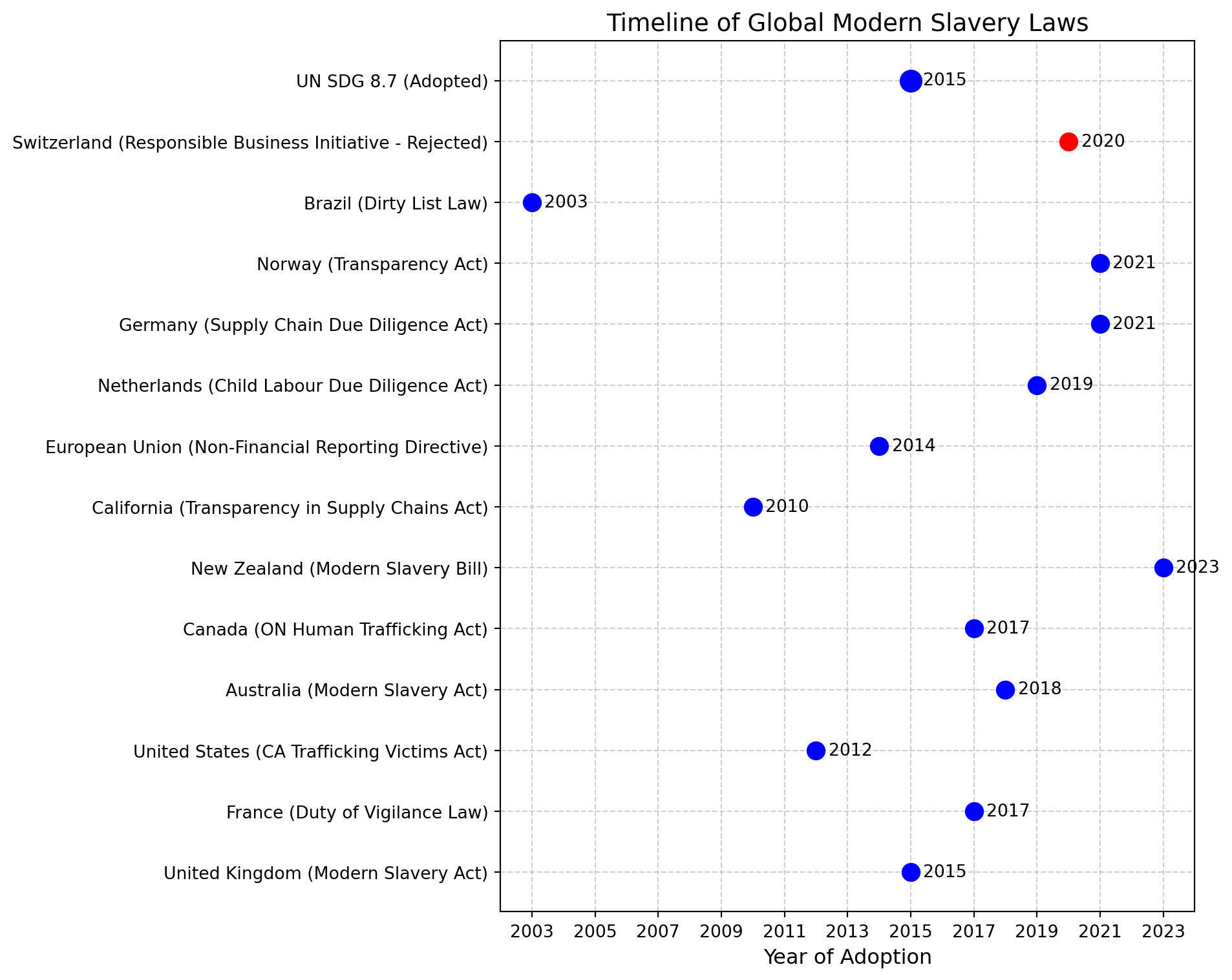

In 2023, an estimated 50 million people were in slavery around the world; lack of supply chain visibility hides forced labor and exploitation of undocumented migrants in agricultural work; 71% of enslaved people are estimated to be women. (Borrelli et al., 2023; Kunz et al., 2023). (Christ & V Helliar, 2021) estimates 20 million people are ‘stuck inside corporate blockchains’. The Global Slavery Index measures the considerable ‘import risk’ of having slavery inside its imports (Walk Free, 2023). (Hans van Leeuwen, 2023) slavery affects industries from fashion to technology, including sustainability enablers such as solar panels. The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates 236 billion USD are generated in illegal profits from forced labor (International Labour Organization, 2024). On the global level, the United Nations SDG target 8.7 targets to eliminate all forms of slavery by 2025 however progress has been slow (The Minderoo Foundation & Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, 2020).

The California Transparency in Supply Chains Act which came into effect in 2012 applies to large retailers and manufacturers focused on pushing companies to to eradicate human trafficking and slavery in their supply chains. Similarly, the German Supply Chain Act (Gesetz über die unternehmerischen Sorgfaltspflichten zur Vermeidung von Menschenrechtsverletzungen in Lieferketten) enacted in 2021 requires companies to monitor violations in their supply chains (Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung, 2023; Stretton, 2022).

The Modern Slavery Act has been passed in several countries starting with the U.K. in 2015, yet commodification of human beings is still practiced worldwide (UK Parliament, 2024). (Mai et al., 2023) finds the quality of the reporting remains low among FTSE 100 (index of highly capitalized listings on the London Stock Exchange) companies. Not everyone is in favor of more stringent labor practices either. Voters in Switzerland rejected the responsible business initiative in 2020 while the country is a global hub for trading commodities. “Switzerland has a hand in over 50% of the global trade in coffee and vegetable oils like palm oil as well as 35% of the global volume of cocoa, according to government estimates” (Anand Chandrasekhar & Andreas Gefe, 2021) begging the question can Swiss traders have more scrutiny over what they trade.

Figure 4: Slavery Laws

Slavery is connected to environmental degradation, and climate change (Decker Sparks et al., 2021). Enslaved people are used in environmental crimes such as 40% of deforestation globally. Cobalt used in technological products is in risk of being produced under forced labor in the D.R. Congo (Sovacool, 2021). In India and Pakistan, forced labor in brick kiln farms is possible to capture remotely from satellite images (Boyd et al., 2018). In effect, the need for cheap labor turns slavery into a subsidy keeping prices lower, and environmental degradation happening.

While reducing slavery in the supply chain sets very low bar for ESG, another aspect of supply tracing is the treatment of workers and working conditions. Currently, one of the largest factory compliance platforms - Fair Factories Clearinghouse (FFC) - covers 149 countries with standardized auditing in the apparel and consumer goods industries, monitoring over 40 thousand workplaces and facilitating over 100 thousand workplace assessments by its members (FFC - Fair Factories ClearingHouse - Compliance Solutions, n.d.). At a similar scale, Sedex spans 170 countries (Novotny, 2025). Nonetheless, with so much auditing happening, there are still cases were people fall through the cracks. Another wave of companies that create “worker voice apps”, intend to “give the supply chain a voice” by connecting workers directly to the consumer (even if anonymously, to protect the workers from retribution), include CTMFile, Alexandria, and PrimaDollar (PrimaDollar Media, 2021; Tim Nicolle, 2021; Worker Voice, 2022). If people working at the factories can directly report working conditions to a safe and anonymous tool, it could serve as a data source for further investigation of labor issues. While there are certainly pitfalls to this approach, one could imagine assigning each factory a social score based on the S-band of their general ESG performance.

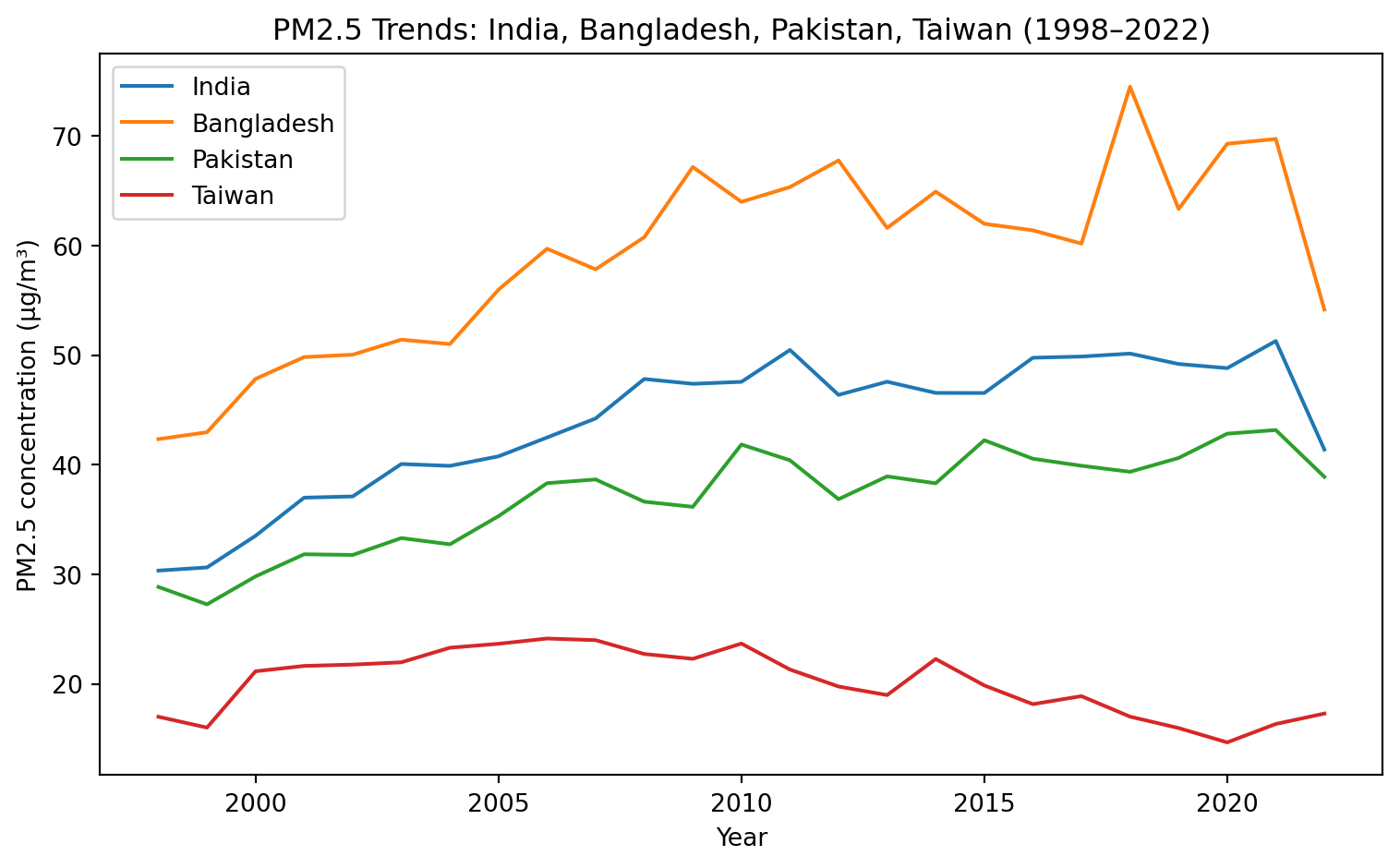

These issues do not pertain only to legacy industries. With the increase of gig-work, platform economy companies have been criticized for their lack of concerns for workers rights (S in ESG). In the absence of continuous assessment, sometimes intrepid journalists come in to cover the issues. One example is the coverage by (Siddiqui et al., 2024), using portable Atmotube Pro air pollution tracking devices (the same device I use myself) to document how gig workers across South Asia, from India to Bangladesh to Pakistan are subjected to pollution, finding PM2.5 exposure 10x over the WHO daily guideline, shortening lives (according to the Air Quality Life Index) by 11.9 years in New Delhi, 8.1 years in Dhaka, and 7.5 years in Lahore, respectively. Air quality varies dramatically between places, however taking the global average in 2022, if fine particulate pollution were reduced to meet the WHO guideline, a person would have gained 1 year and 11 months of life expectancy (Institute for Climate and Sustainable Growth, 2022).

Figure 5: Air Quality in Taiwan vs South-East Asia

The above charts shows a comparison of air quality trends in South Asia vs Taiwan; while air pollution has increased in India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, Taiwan has returned to the pollution levels of 1990s.

Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance: Criteria for a Shared Language

Since the 1970s, international bodies, governments, and private corporations have developed sustainability measurement metrics, the prominent one being ESG (Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance) developed by the UN in 2005. This rating system has already been implemented or is in the process of being adopted on stock markets all over the world and has implications beyond the stock markets, allowing analysts to measure companies’ performance on the triple bottom line: the financial, social, and environmental metrics.

Taiwan has listed ESG stocks since 2017 and was hailed by Bloomberg as a regional leader in ESG reporting (Grauer, 2017). In December 2017, the FTSE4Good TIP Taiwan ESG Index was launched, which tracks ESG-rated companies on the Taipei stock market (Taiwan Index, 2024). Nasdaq Nordic introduced an ESG index in 2018, and Euronext, the largest stock market in Europe, introduced an ESG index and a series of derivative instruments in the summer of 2020 (Euronext, 2020).

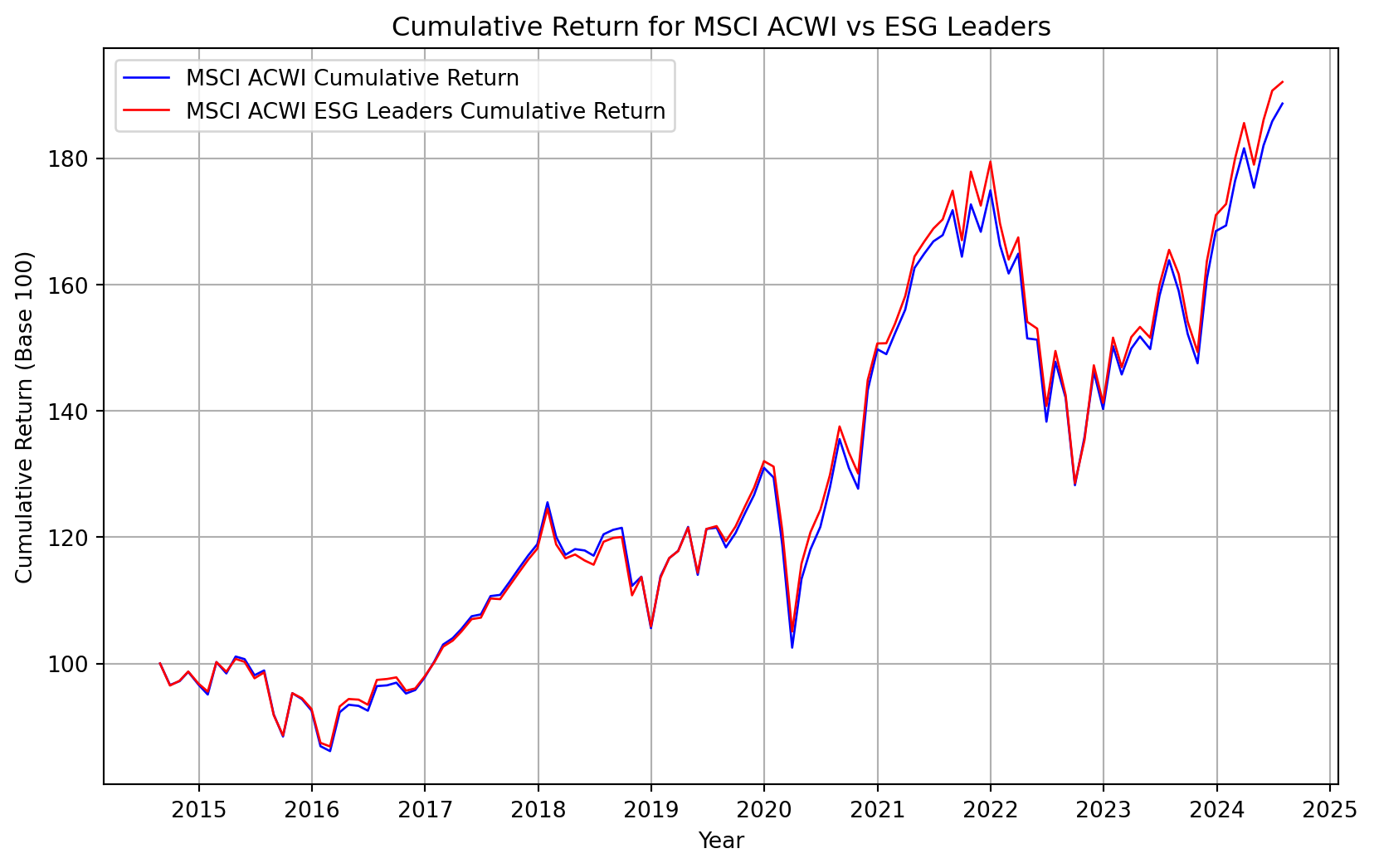

(The Importance of ESG Measurement and Canada’s Opportunity for Improvement, 2022) suggests ACWI ESG leaders outperform the non-ESG screened ACWI based on comparing MSCI indexes. It’s notable that ACWI ESG started to outperform the traditional ACWI only in the past few years (evidence that capital markets are starting to price sustainability, but still inconsistently). Nordic Climate Transparency Leadership analysis of Nasdaq OMX Nordic 120 companies: “companies with higher quality climate reporting also provide higher returns”. In contrast, (D. Luo, 2022) found firms with a lower ESG score are more profitable.

Figure 6: ESG Funds vs Non-ESG Funds

Towards Green Transparency - But Who Does the Rating?

Trucost, a company launched in 2000 to calculate the hidden environmental costs of large corporations and advance circular-economy practices was acquired in 2016 by S&P Dow Jones Indices, which by 2019 became a part of its ESG product offering (Indices, Oct 03, 2016, 08:30 ET; Mike Hower, Dec 9, 2015 7am EST; S&P Rolls Out Trucost ESG Data to Its Customers, 2019; Toffel & Sice, 2011). It’s parent company S&P Global also acquired RobecoSAM’s ESG rating business, consolidating S&P’s control of ESG ratings (George Geddes, 2019).

Figure 7: Company Performance

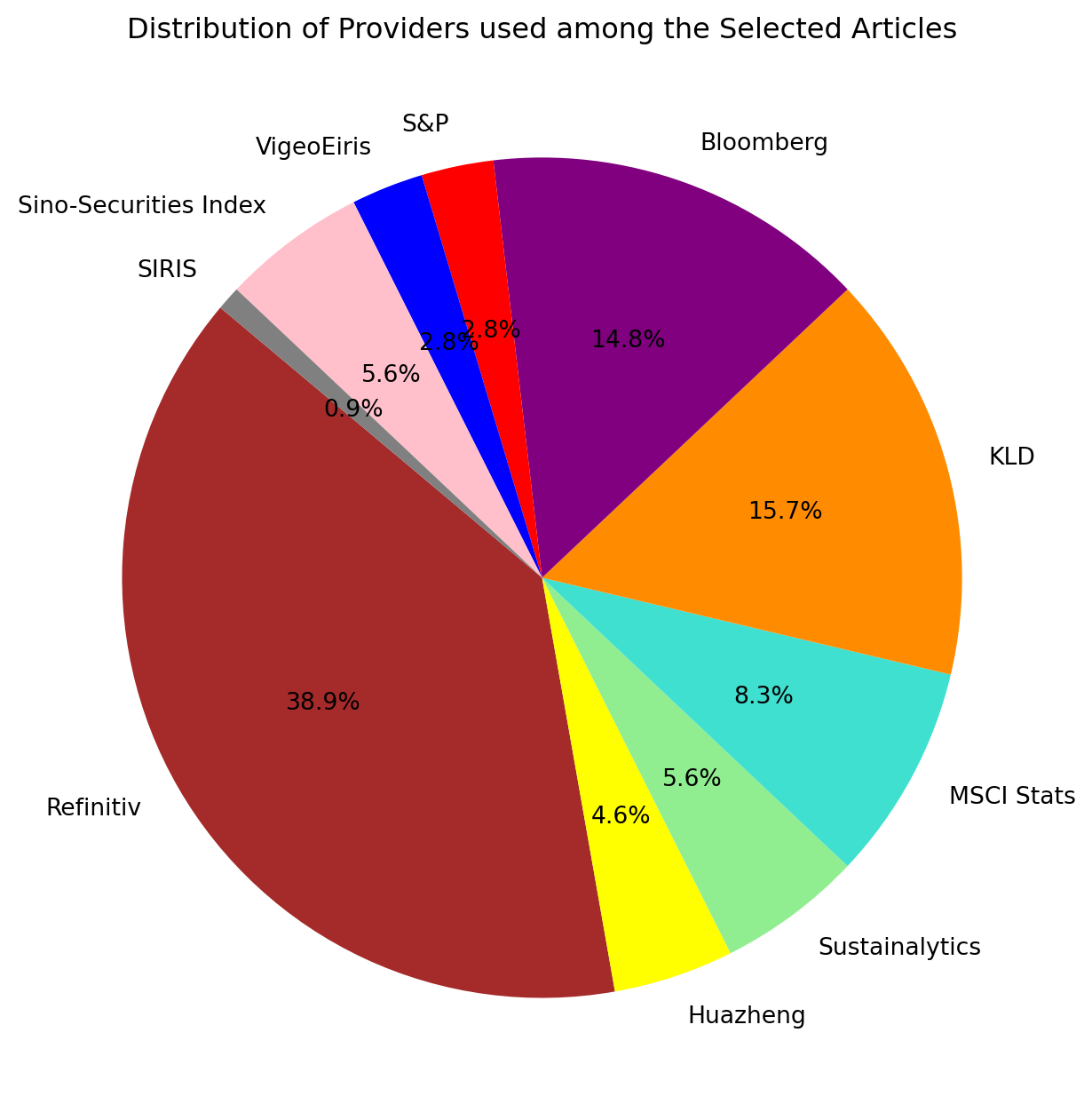

A meta-review of 136 research articles discovered the following ESG-rating agencies.

Figure 8: ESG Rating Agencies

Figure 9: Types of Investment Funds

Three frameworks for corporate to think about ESG compliance is to position their company on the MEET, EXCEED, and LEAD scale based on the size, complexity and available resources of the company.

Robeco’s survey of 300 large global investors totaling $27T under management found biodiversity-protection is increasingly a focus-point of capital allocation (Robeco, 2023).

ESG Success Depends on Good Governance: Boards, Policy, and Investor Pressure

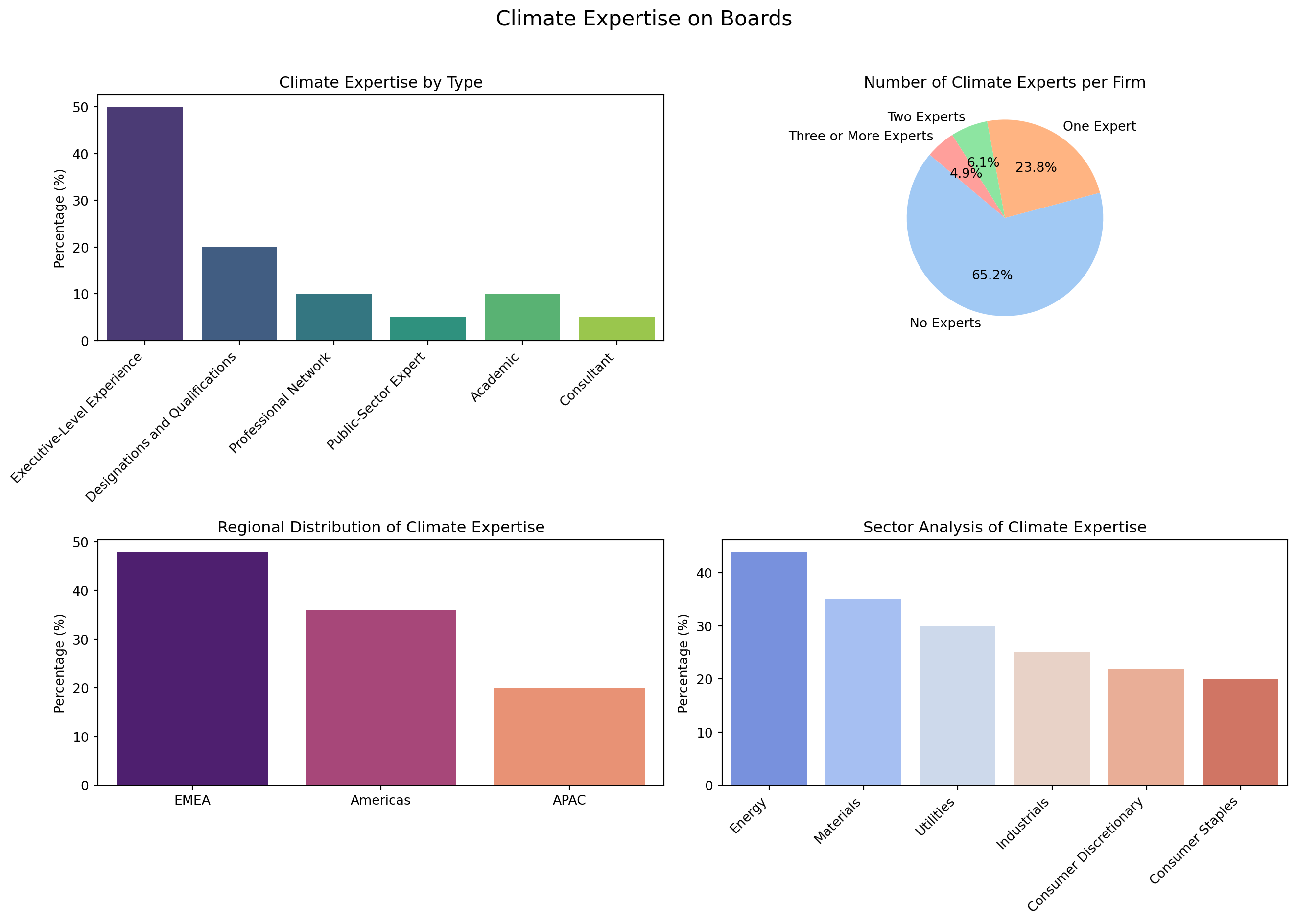

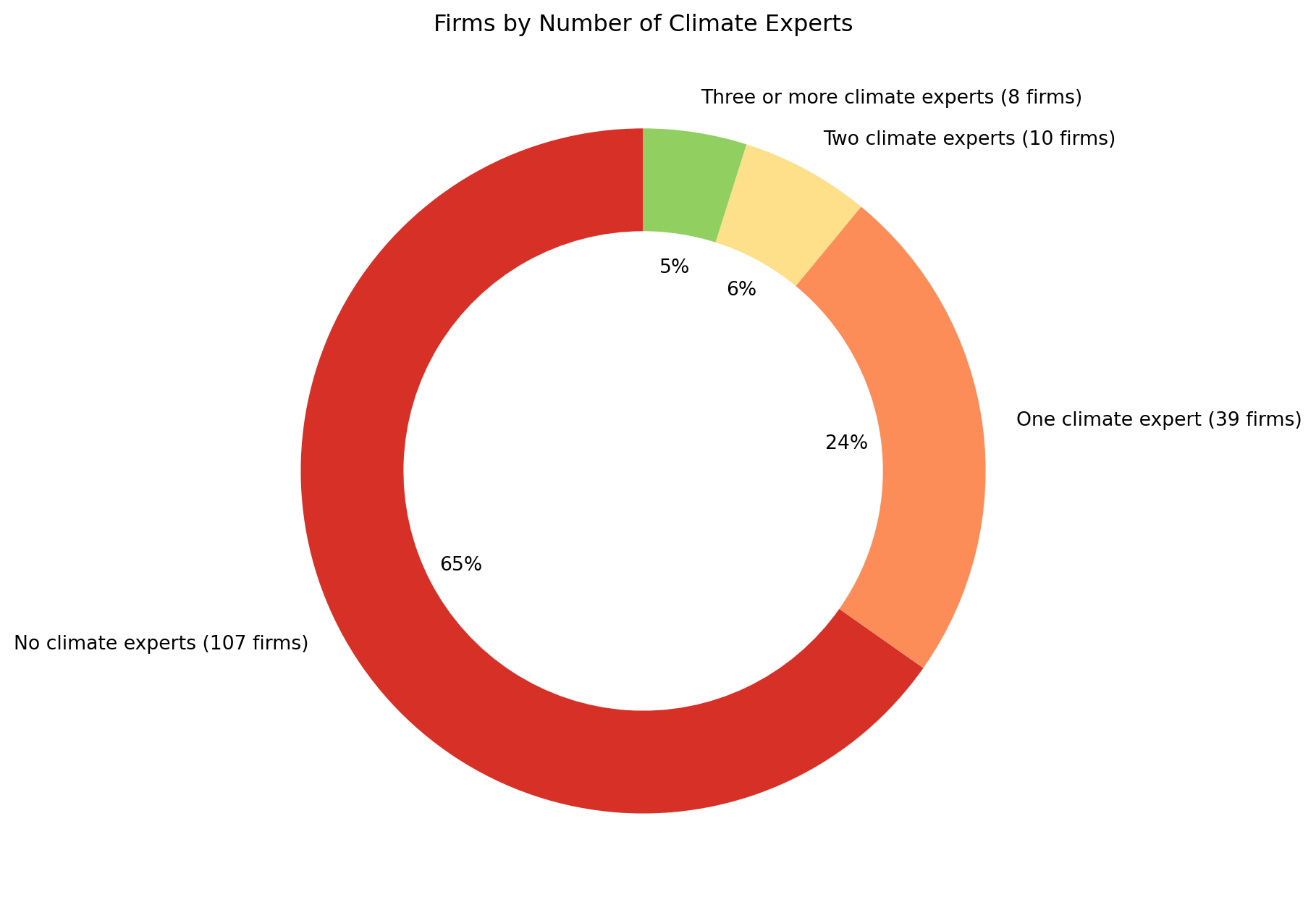

Governance in ESG is the G that makes E and S happen - or put in another way: governance drives social and environmental initiatives at companies. Yet MSCI research finds company boards severely lacking in climate experts; among the 164 large CO2eq emitters (1986 directors in total) benchmarked by the Climate Action 100+ alliance, 65% have no board member with demonstrated climate expertise, highlighting a major governance gap (Climate Action 100+, 2023; Sommer et al., 2024).

| Region | Companies (n) | ≥ 1 Climate Expert (%) | ≥ 1 Expert (count) | No Experts (%) | No Experts (count) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMEA | 52 | 48 % | 25 | 52 % | 27 |

| Americas | 61 | 36 % | 22 | 64 % | 39 |

| APAC | 51 | 20 % | 10 | 80 % | 41 |

Figure 10: Lack of Board Members With Sustainability Expertise

Figure 11: Large Carbon Emitters Lack Sustainability Experts

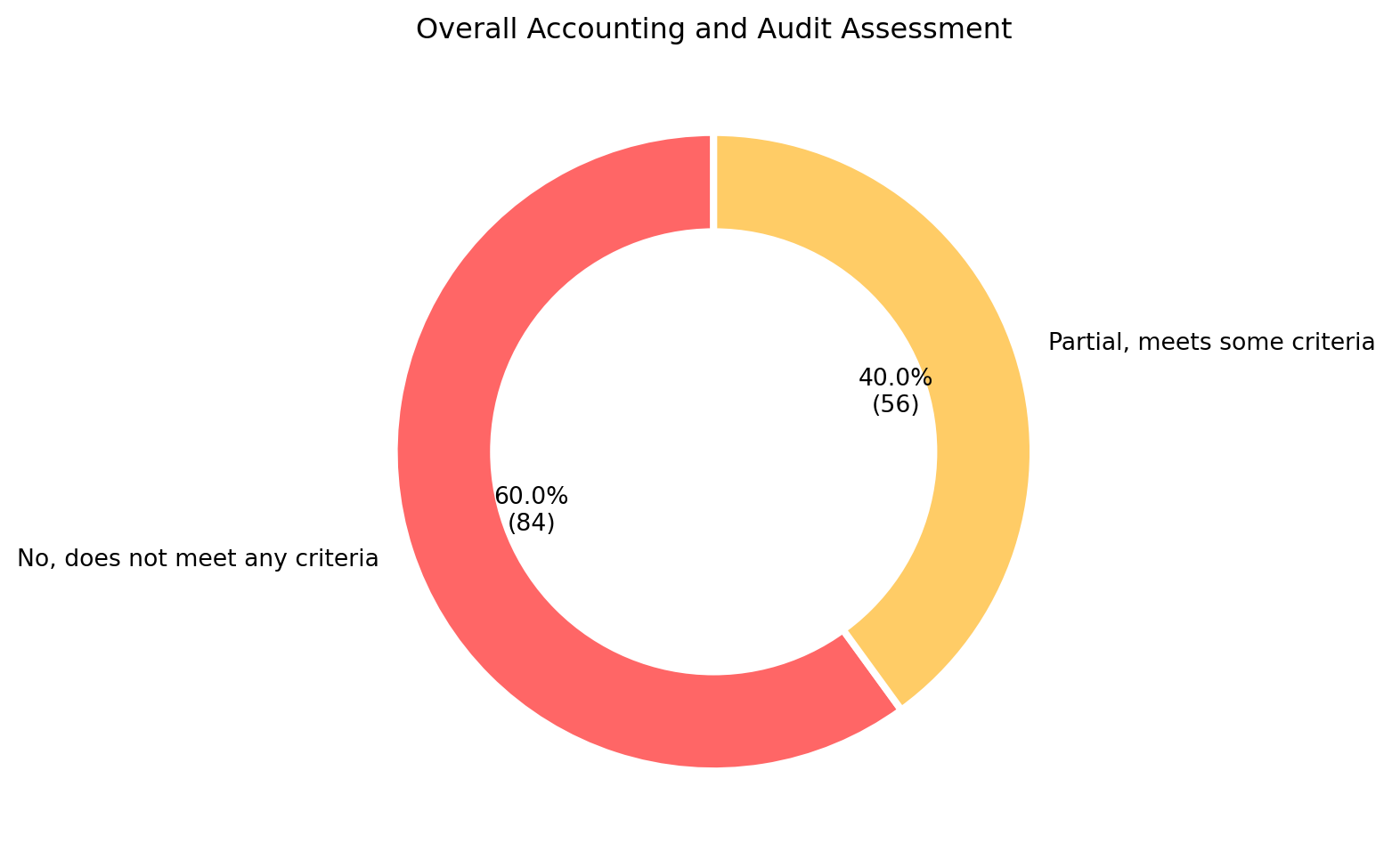

Most companies do not meet the criteria (Climate Action 100+, 2023).

Figure 12: Large Carbon Emitters Do Not Meet Sustainability Criteria

Lack of leadership is a key challenge for sustainability. (Capgemini, 2022) “Many business leaders see sustainability as costly obligation rather than investment in the future” was the finding from the Capgemini Research Institute’s report “Why sustainability ambition is not translating to action” surveyed 2,004 executives from 668 large organizations; 53% of leaders view sustainability initiatives as a financial burden, believing the costs outweigh the benefits, and only 21% agree that the business case for sustainability is clear, underscoring a pervasive leadership gap that treats sustainability as a costly obligation.

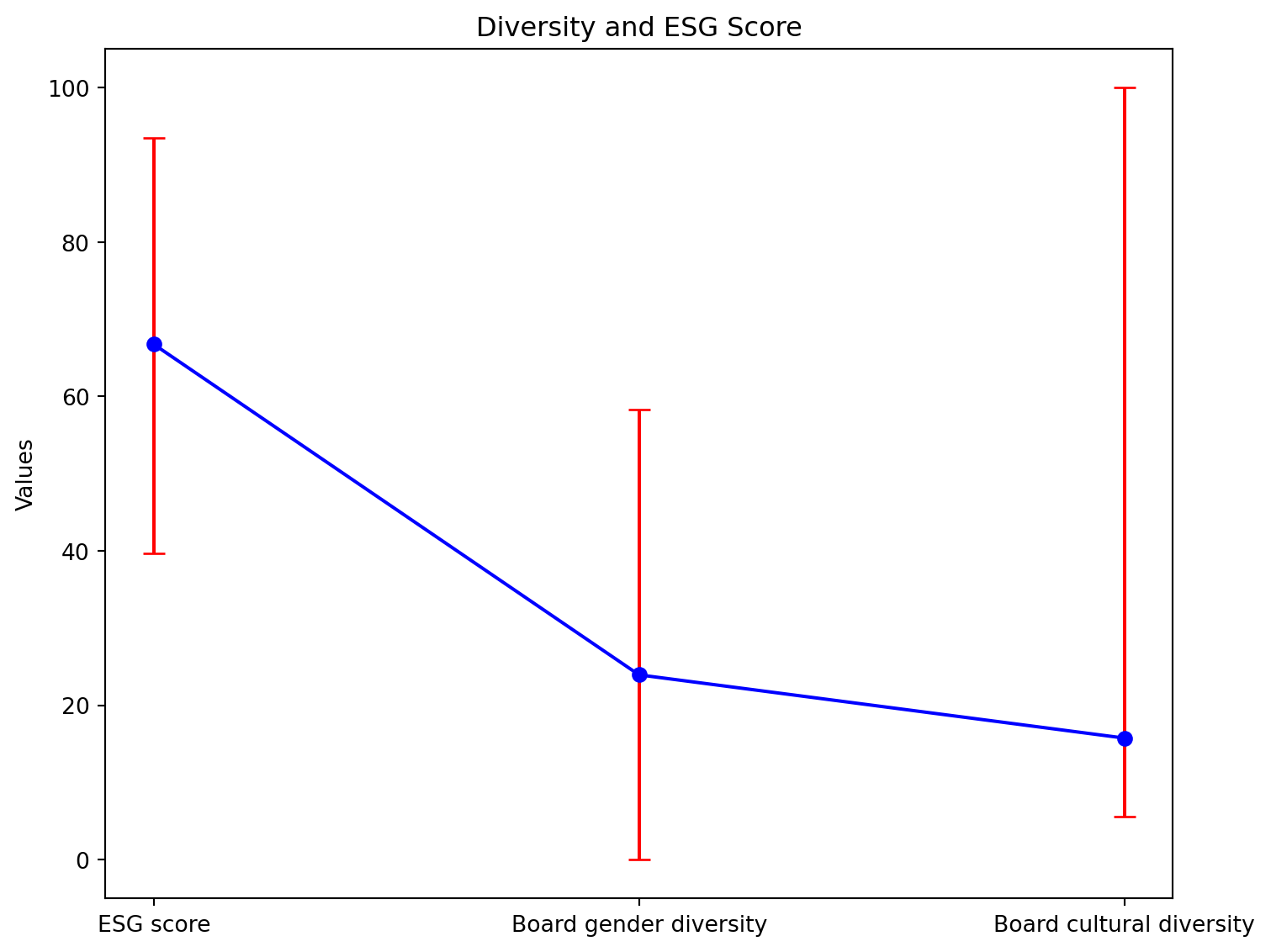

A systematic study of 153 peer-reviewed papers of ESG literature published between 2006 and 2023 around the world reports the major determinants of high ESG performance are board member diversity, firm size, and CEO attributes; actively diversifying boards, especially adding members with sustainability expertise, and aligning executive compensation with ESG targets to translate strategic ambitions into operational results, may boost ESG outcomes (Martiny et al., 2024).

Figure 13: Board Diversity

The CEO of the Swedish clothing producer H&M - one of the largest fast-fashion companies in the world -, recognized the potential impact of conscious consumers as a threat (Hoikkala, 2019) and at the same time launched a clothes repair service in partnership with the Norwegian start-up Repairable, as reported by the Norwegian Sustainability Hub (S HUB, 2018). This kind of discrepancies are all over the place. While Coca-Cola is the largest plastic polluter in the world, at the same time it runs the “World Without Waste” program which supports packaging recycling around the world, reporting achieving a global 90% recycling rate for Coca-Cola packaging (Break Free From Plastic, 2024; Simões-Coelho et al., 2023). Large corporations such as Coca-Cola and Nestle also support the biodiversity law, calling for a level playing field for business limit biodiversity risk (Greens EFA, 2023).

Many large businesses have tried to find solutions by launching climate-focused funding. (Korosec, 2021) reports that Amazon’s 2B USD to a Climate Pledge Fund earmarked to fix climate problems is invested in energy, logistics, and packaging startups, which will reduce material waste. “Good intentions don’t work, mechanisms do,” Amazon’s founder Bezos is quoted as saying in (Clifford, 2022). Walmart is taking a similar approach, having launched a project in 2017 to set CO2 reduction targets in collaboration with its suppliers (Walmart, 2023). These examples underline how money marketed as climate funding by retail conglomerates means focus on reducing operational cost of running their business through automation and material savings.

Shareholders can leverage their numbers and join forces in order to affect the board members of large corporations. For example, the As Your Sow NGO aims to champion CSR through building coalitions of shareholders and taking legal action, including the Fossil Free Funds initiative which researches and rates funds’ exposure to fossil fuels finance and its sister project Invest in Your Values rates retirement plans offered by employers (mostly US technology companies) (As You Sow, 2024a, 2024b).

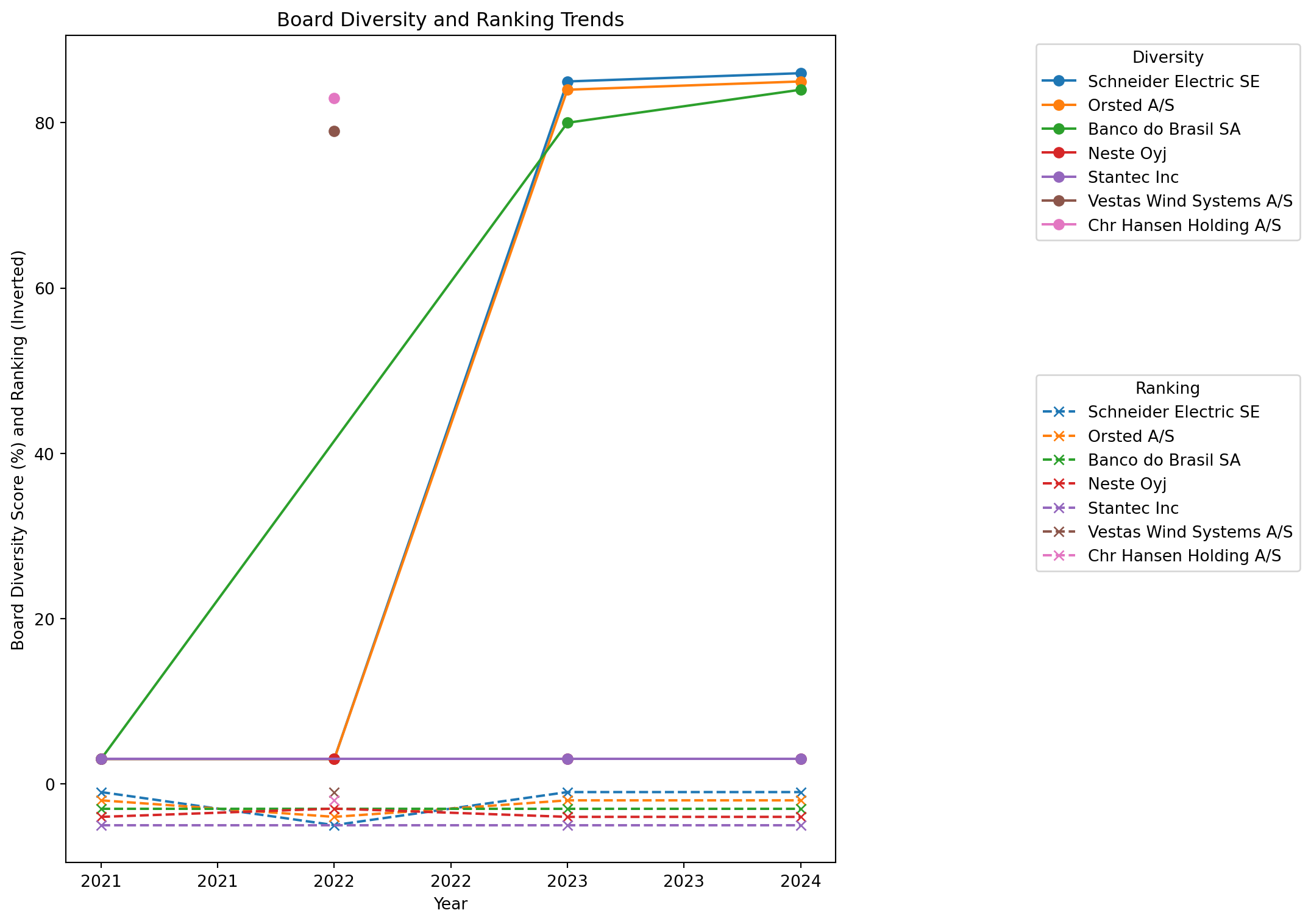

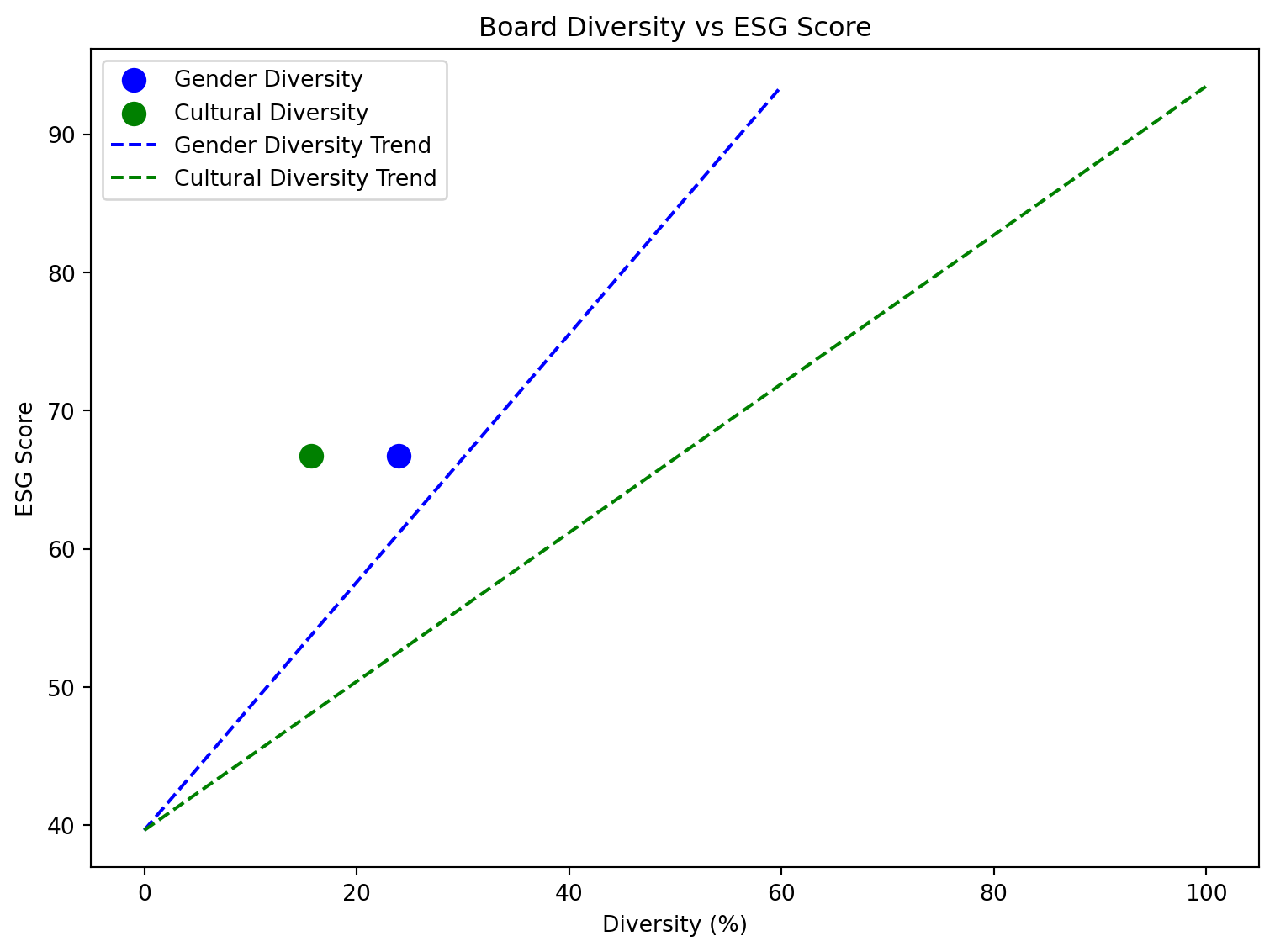

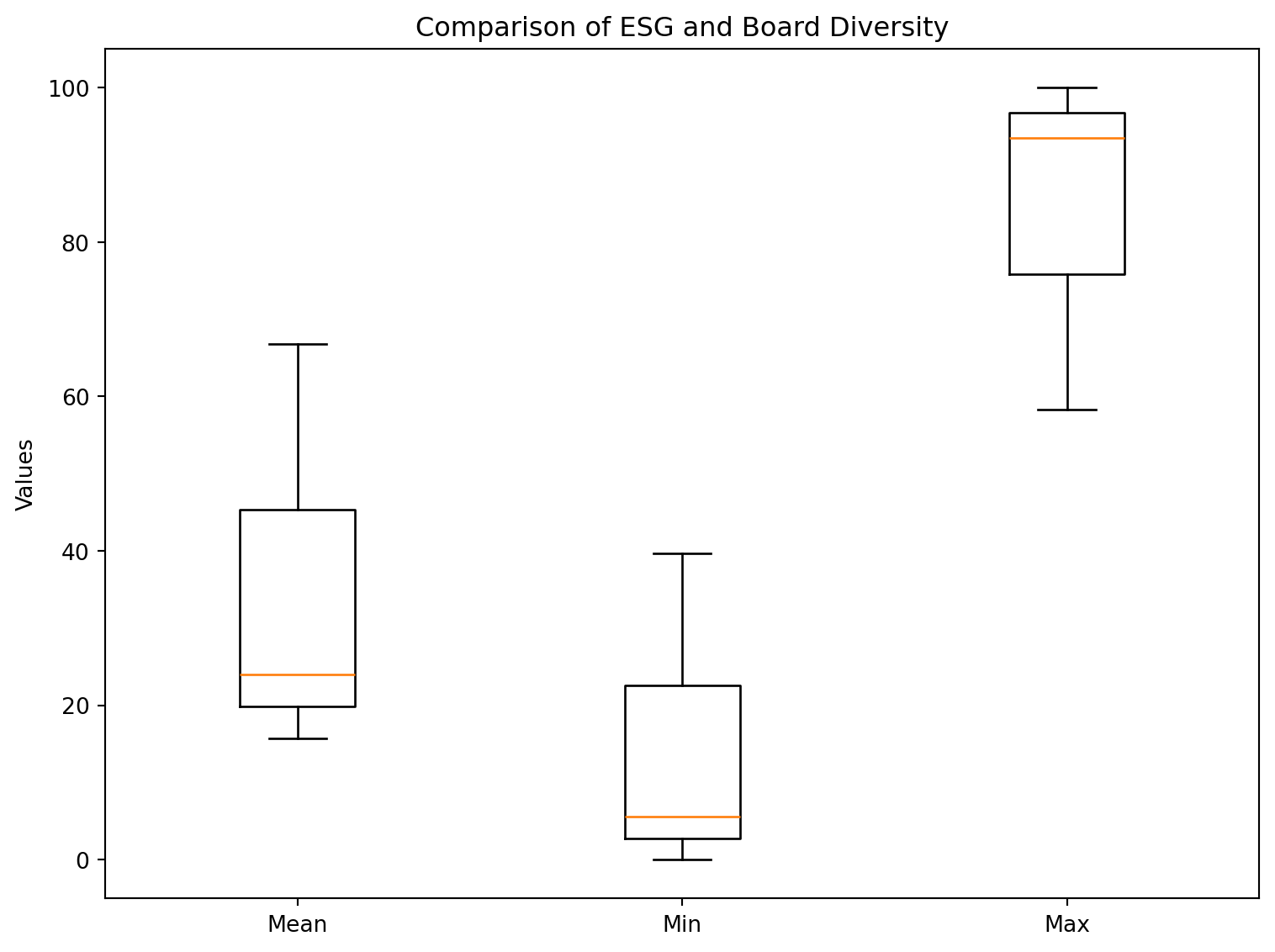

Board diversity in the top 5 sustainable companies in 2024 based on Corporate Knights rankings (Corporate Knights, 2024).

(a) Simplified comparison chart for board diversity (gender and cultural) vs ESG score

(b)

(c)

Figure 14

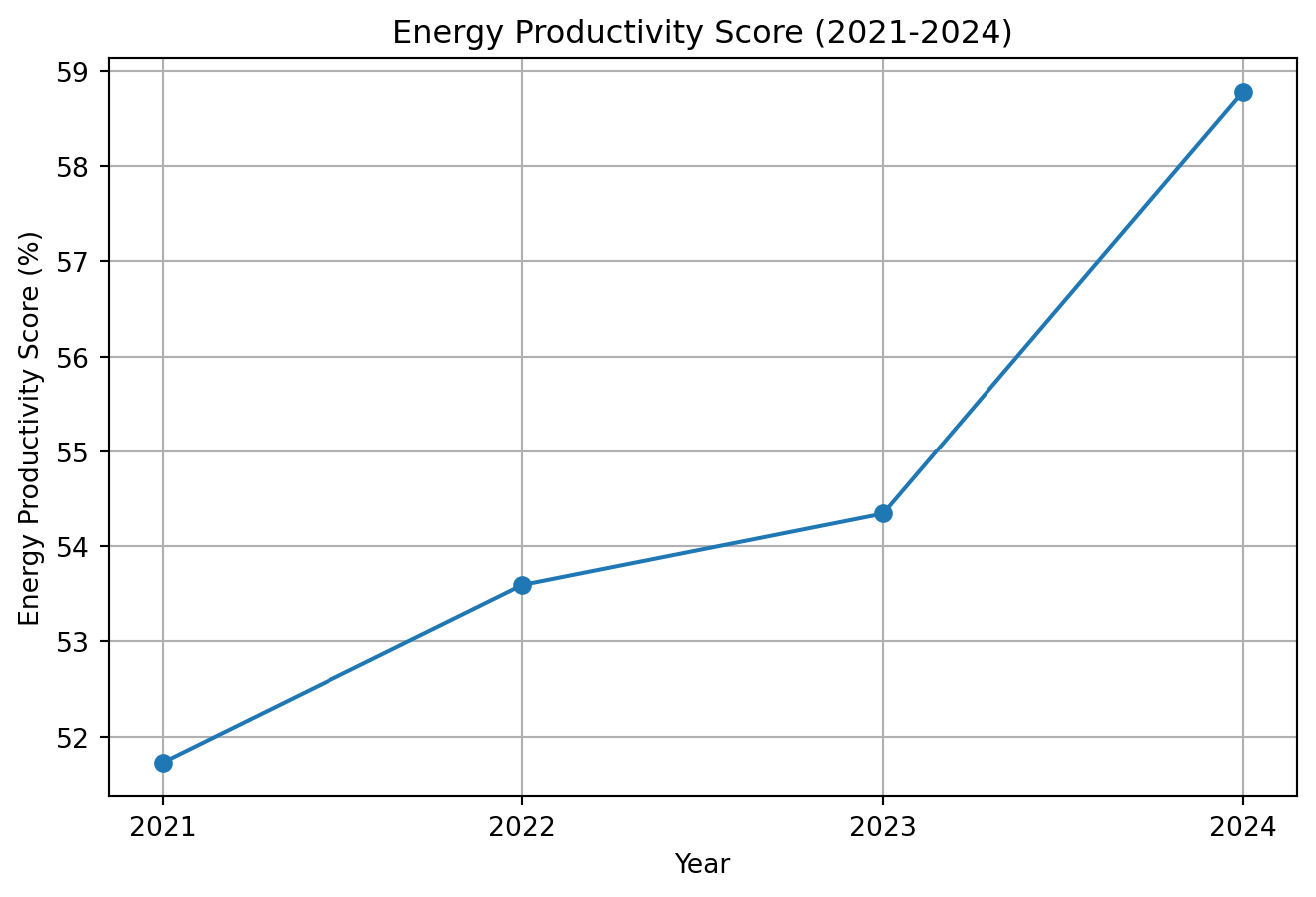

ESG Success Depends on Digitization and GenAI

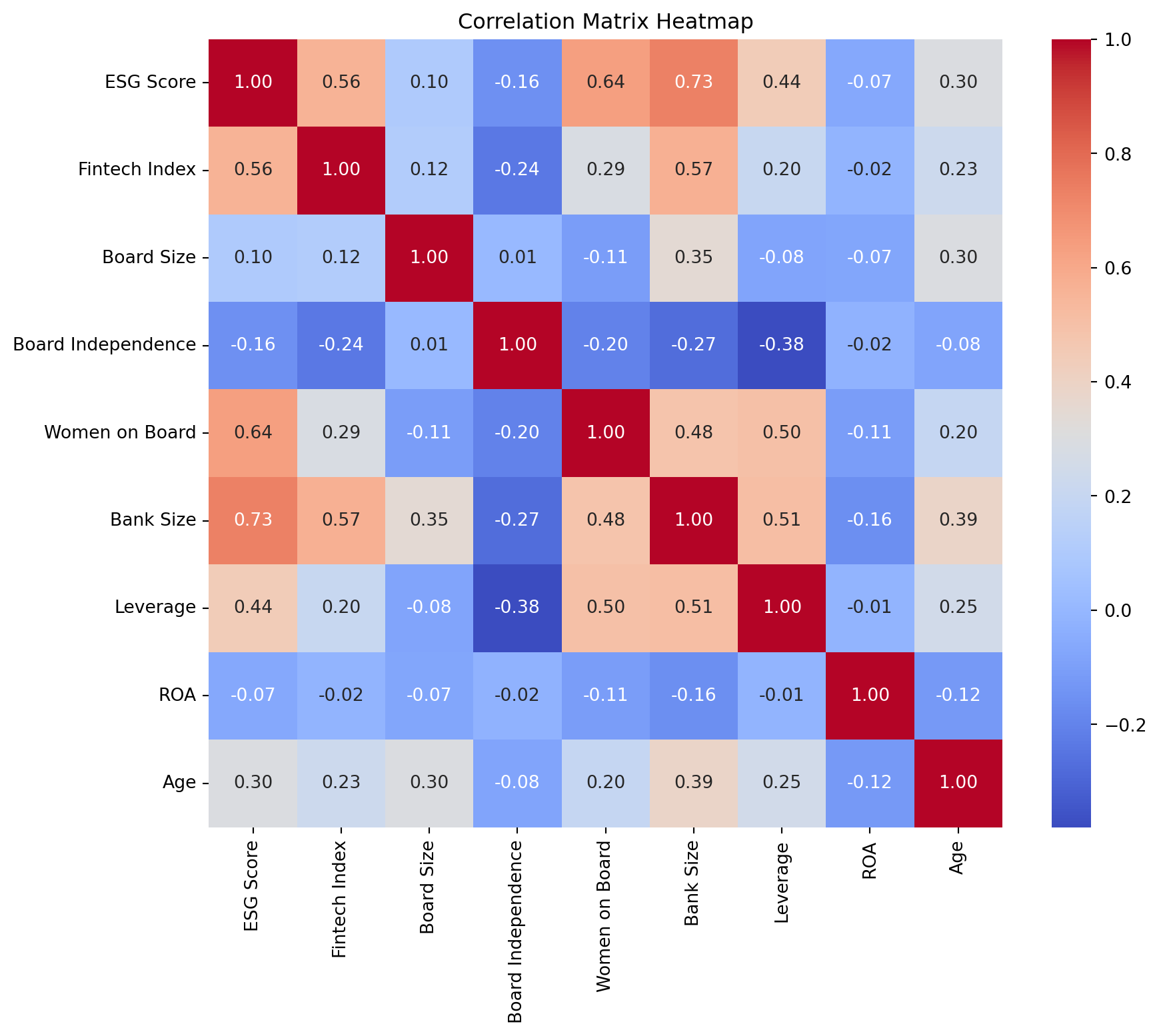

In the U.S. and European banking sector (Dicuonzo et al., 2024) performed an analysis of 1551 banks, of which only 180 banks disclosed sufficient ESG data for comparison, building a Fintech Adoption Index; the key findings included a positive correlation between Fintech Index and ESG Scores, suggesting the adoption of technology has a statistically significant influence on better environmental stewardship, social and governance quality. Even better predictors of a high ESG score were Board Gender Diversity (Women on Board), the Size of the Bank, and Board Independence (governance structures with more independent directors could be more socially and environmentally responsible).

Figure 15: Fintech Adoption Predicts Higher ESG

The ability to build sustainability into the organization requires deep understanding of how the complex structure works and what drives change and innovation within business units. (Jim Boehm et al., 2021) distilled key strategies from the banking sector to speed up digital transformation, while improving risk management and compliance (see table below).

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Enterprise-level Risk Taxonomy | A unified classification system that defines and categorizes all risk types across the entire organization. |

| Embedded Controls in Agile Delivery | Risk-and-compliance integration directly into agile development sprints (a type of management style in building software) to catch issues as code is written. |

| Cross-functional Risk–Business Collaboration | Joint ownership of risk by compliance teams and business units, ensuring controls are practical and business-aligned. |

| Metrics-driven Monitoring | Continuous tracking of key risk indicators through quantifiable metrics to spot trends and trigger alerts. |

| Proactive Remediation | Early detection and rapid resolution of control defects before they escalate into larger compliance or security gaps. |

| Continuous Capability Building | Ongoing training and tooling updates; best-practice sharing to keep risk-management skills and processes current. |

These banking transformation strategies sit alongside strict regulatory requirements, such as Know Your Customer (KYC), and emerging technologies like generative AI, which is already reshaping compliance workflows. (Rahul Agarwal et al., 2024) details how genAI is being used for the purposed of compliance and comprehensive risk assessment in modern banking.

| GenAI Use Case | Description |

|---|---|

| Regulatory Compliance | Automate policy-document triage: draft regulatory-change summaries and flag emerging rules, then generate compliance manuals. |

| Financial Crime | Generate suspicious-activity reports; streamline AML/KYC checks; identify anomalous transaction patterns. |

| Credit Risk | Synthesizing credit-risk reports on demand by pulling together relevant financial data from a variety of sources, resulting in faster borrower risk assessments. |

| Analytics and Modeling | Build and validate risk models; run scenario analysis; summarize complex data sets for insights. |

| Cyber Risk | Monitor threat-intelligence feeds; draft incident-response reports; automatically search for, and possibly even patch security gaps. |

| Climate Risk | Distill lengthy climate-scenario reports; visualize key metrics; accelerate enterprise-level climate-risk assessments. |

In the context of China’s industrial modernization, (Lu & Li, 2023) finds that digitization is the pathway to increased Environmental Information Disclosure (EID) and Green Innovation, correlating with increased numbers of green patents and sustainable R&D projects.

While ESG is riddled with problems, it has started a common language - the advice consultancies are providing to banks make use this common language to helps banks to sell strategical alignment for long-term institutional sustainability in terms of environmental, social, and governance performance. PWC suggests “asset managers educate their staff and client base. It will be critical to build stronger ESG expertise among their employees by up-skilling existing staff on ESG principles and strategically scout for and integrate more diverse and ESG-trained talent” (PWC, 2020).

In general, a futures contract is an agreement to buy or sell a market index at a fixed price on a set date, locking in today’s price for the future. The exchange’s clearinghouse guarantees the trade, so one doesn’t have to worry about the other side not honoring the deal. ESG futures specifically, are financial derivatives, standardized contracts, which allow investors to hedge or speculate on the future performance of ESG-compliant investments. Some ESG futures contracts include the E-mini S&P 500 ESG futures (on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, a large derivatives exchange), which track the U.S. S&P 500, while skipping companies with poor ESG scores, letting one bet on or hedge “sustainable” American companies with large market capitalization; notably, the index has recently been renamed to S&P 500 Scored & Screened Index, without a specific mention of the acronym ESG, while keeping the methodology unchanged, presumably for marketing purposes in the changing political landscape (CME Group, 2025). In Europe, the STOXX Europe 600 ESG-X futures (on the Eurex stock market) let one trade Europe’s top ESG-screened companies, with cash settlement and the same margin rules as regular (non-ESG) index futures (Deutsche Börse Group, 2025; Harding, 2019). Globally, the MSCI Sustainability and Climate Change futures (on the Intercontinental Exchange) cover global and regional ESG benchmarks, allowing one to take a position on low-carbon or Paris Climate Agreement-aligned stock indices anywhere in the world (Intercontinental Exchange, 2025). The CFI2Z4 Carbon Emissions Futures tool tracks live coverage of ICE EU Allowance futures priced in EUR per tonne, with real-time quotes as well as historical charts, enabling traders to monitor and analyze the compliance-phase carbon market (Investing.com, 2024). Specifically in Taiwan, the FTSE4Good TIP Taiwan ESG futures (on TAIFEX, Taiwan Futures Exchange), launched in June 2020 to follow a basket of Taiwanese stocks that meet global ESG standards (TAIFEX, 2025).

ESG Accessibility: Curbing Corruption with Real-time Data Streams and Product Lifecycle Traceability

For AI-powered assistants to be able to provide guidance, metrics are needed to evaluate sustainable assets, and ESG provides the current state-of-the-art for this. The largest obstacle to eco-friendly investing is greenwashing where companies and governments try to portray an asset as green when in reality it’s not. A personal investing assistant can provide an interface to focus on transparency, highlighting data sources and limitations, to help users feel in control of their investment decisions, and potentially even provide large-scale consumer feedback on negative practices.

However, fundamentally, unless there is significant headway in curbing greenwashing, companies today use ESG as a marketing tool - but it could achieve much more. One of the key emerging issues is that ESG is an annual report not real-time, actionable data. (Sahota, 2021) argues that “[T]hanks to other emerging technology like IoT sensors (to collect ESG data) and blockchain (to track transactions), we have the infrastructure to collect more data, particularly for machine consumption. By measuring real-time energy usage, transportation routes, manufacturing waste, and so forth, we have more quantifiable ways to track corporations’ environmental performance without relying purely on what they say.”

For corporations to respond to the climate crisis, they are expected to become more digital and data-driven. Requirements for ESG compliance has given rise to a plethora of new monitoring tools. There’s a growing number of companies helping businesses to measure CO2eq emissions in through their entire product lifecycle. In order to improve product provenance, blockchains offer transparency. Several enterprise blockchain offerings from vendors such as Hyperledger Fabric and ConsenSys use immutable supply‐chain ledgers to record origin, certifications, and product movements end‐to‐end (Blockchain Companies Team Up To Track ESG Data, 2021). Blockchain’s immutable data and programmable incentives enable transparent ESG tracking, secure carbon‐credit registries and tokenized rewards that align corporate behavior with climate goals (Ganu, 2021). Sourcemap’s supply chain mapping platform provides tooling to know your suppliers’ suppliers, monitoring every tier of company supply chains, continuously collecting and checking the integrity of supplier data, using 3-party registries and watchlists, real-time transaction traceability, creating an audit trail for instantly detecting fraud or non-compliance with effective regulations and due-diligence laws (Sourcemap, 2025). The founder of Sourcemap, Leonardo Bonanni, started out with doing product autopsy in 2015 to assess product sustainability (<< Fast fashion >>, 2023).

(Ratkovic, 2023; Tim Nicolle, 2021) believe that real-time ESG data is more difficult to greenwash, because the supply chain data is a significant source of ESG content; a fundamental breakthrough would be surfacing real-time ESG data directly to individual consumers browsing products - be it in physical shops or online, - allowing customers to judge if they want to purchase from this business. (Real Time ESG Tracking From StockSnips, 2021) built a tool - called Stocksnips - to turn unstructured news into daily ESG sentiment signals, starting with about 1000 companies; the sentiment signal shows significant correlation with expert ratings, offering an automated forward-looking gauge of corporate ESG performance. Likewise, LSEG’s MarketPsych ESG Analytics platform mines global news and social feeds for near‐real‐time controversy alerts and ESG risk‐scores with historical data going back to 1998 (LSEG, 2025). Envify aims to automate compliance with the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), by providing a suite of carbon accounting tools (Rajan, 2025). Flowit Estonia automated real‐time CO2eq accounting in 2022 by combining invoices and sensor data to generating instant per‐transaction emission footprints (Indrek Kald, 2022). A startup called Makersite proposes instant sustainability impact from supply chain, deep supply-chain data can surface product–level environmental footprints in minutes instead of months, which they call “Product Lifecycle Intelligence” (Kyle Wiggers, 2022). More recently, Makersite has updated the language they use for promoting their product, now calling it Product Sustainability Modeling (Makersite, n.d.). Apart from product level analytics, there’s sustainability data on source raw materials. CarbonChain rolled out asset-level emissions ratings for individual mines: covering metals including steel, aluminium, nickel, and copper - so product developers can benchmark material sources’ carbon intensity against industry averages (CarbonChain, n.d.).

Payments

Consumer Activists are a Small Minority

Recognition precedes protection, as the Estonian slogan goes: “Õpetame märkama, et oskaksime hoida” / “Learn to notice so we can preserve.” (Tartu loodusmaja, 2019). (Milne et al., 2020) coins the term mindful consumers, who do research and are aware of the impact of their shopping choices. Yet these types of mindful consumers and conscious consumers only make up a small percentage of the entire consumer public, which may make individual action seem close to meaningless.

For consumer activism to become mainstream it needs to much simpler. Sustainable options must become effortless: we need one-click tools that turn everyday spending into votes for circular design, transparent supply chains and mandatory climate disclosures. By setting clear CO2-reduction targets for products, embedding dynamic ESG-risk pricing at point of sale, and harnessing our collective purchasing power, we can push companies to embed sustainability at the core of business, transforming vague ESG ideals into tangible market incentives.

There is plenty of research on if and how sustainable shopping could be possible. Already in 2016, (Klinglmayr et al., 2016) proposed a mobile app to channel “political consumerism” into sustainable shopping through self-regulation: personalized recommendations could be provided by aggregating vast product datasets into distilled advice, empowering individuals follow clear sustainable-shopping rules, discover like-minded peers, and communicate concerns directly to retailers, in theory turning vague ESG ideals into a transparent, data-driven, community-backed approach to sustainable consumption - however the Horizon 2020-funded was only deployed in 2 supermarkets (Estonia and Spain) as a pilot project. In order to understand the needed changes to shopping, (Fuentes et al., 2019) employed a shopping-as-practice ethnography in a Swedish zero-waste grocery store to show that removing packaging requires reinventing the shopping practice itself, e.g. introducing reusable containers, new retail setups, and consumer routines. (Weber, 2021) proposed a sustainable shopping guide in a study which demonstrates that embedding eco-score rankings into a mobile shopping app significantly increases consumers’ selection of low-impact food products by improving decision support and reducing information overload. Consumer psychology is complex and (van der Wal et al., 2016) discusses how status motives make people publicly display sustainable behavior, revealing that shoppers purchase branded reusable bags rather than bring their own, exposing a “paradox of green to be seen” and its hidden environmental costs.

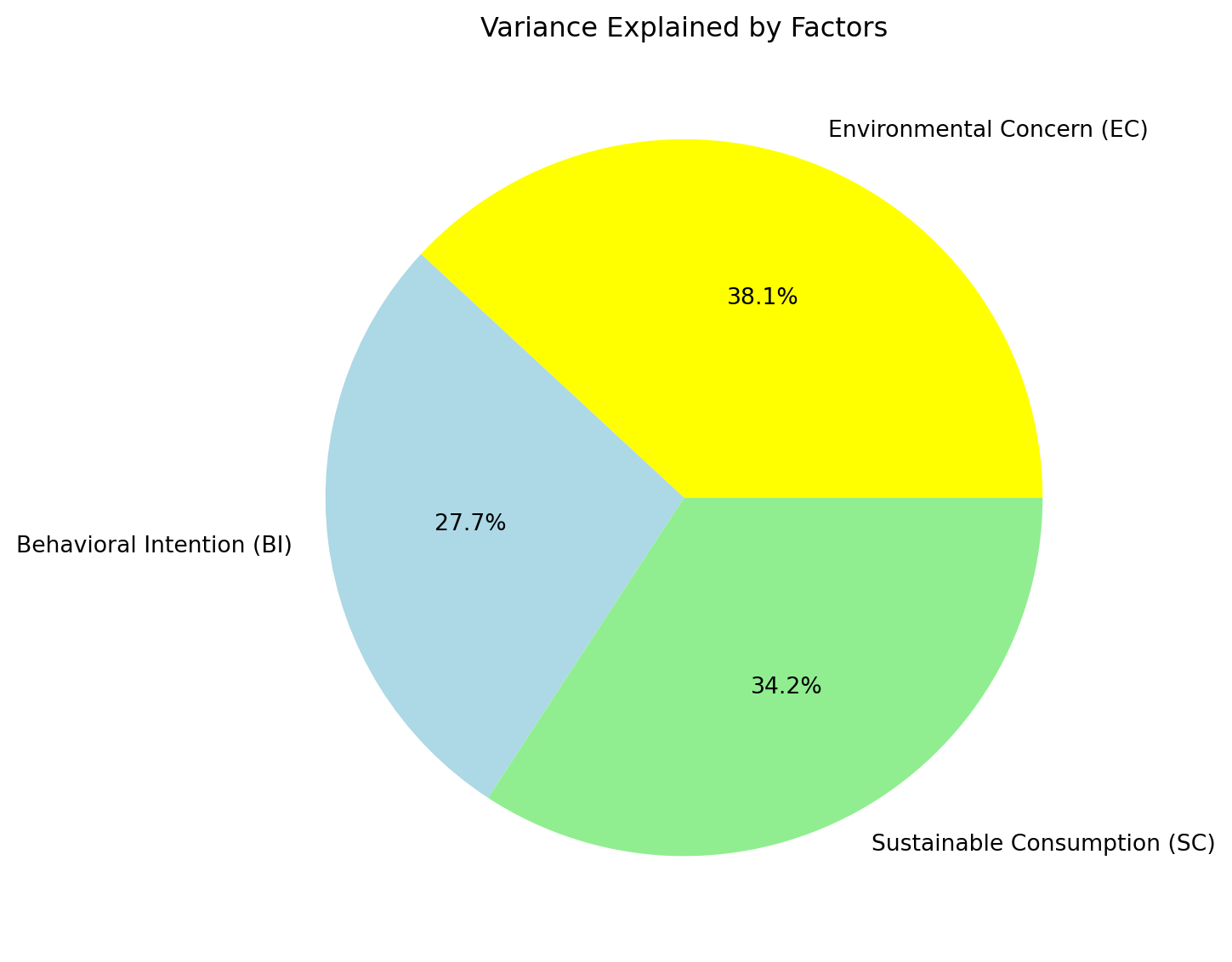

Sustainable consumption relationships in Europe.

(a) Sustainable Consumption

(b)

(c)

(d)

Figure 16

Make use of indexes to compare companies.

Shopping’s Environmental Footprint: Increasingly Driven by Digital Platforms, Social Commerce, AI Assistants

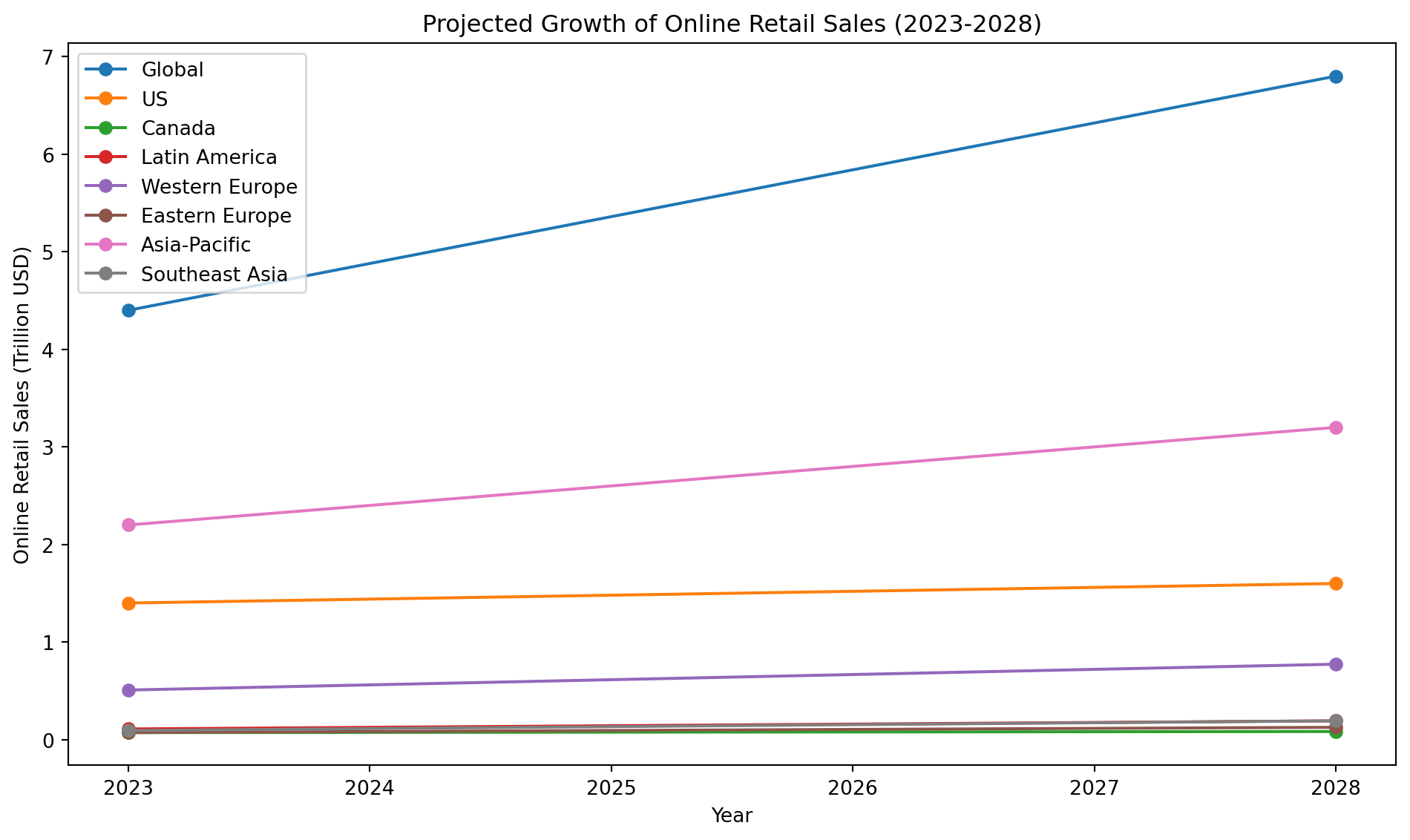

It may seem impossible to turn the tide of consumerism, given the projected growth in online shopping, Single’s day, etc. (Forrester, 2024). However, importantly - more and more consumers are using AI assistants to find alternative products, make shopping lists, which may have an effect on what type of products are bought (Neuron, 2025; Pandya, 2025; Pastore, 2025)

Figure 17: Growth of Consumerism

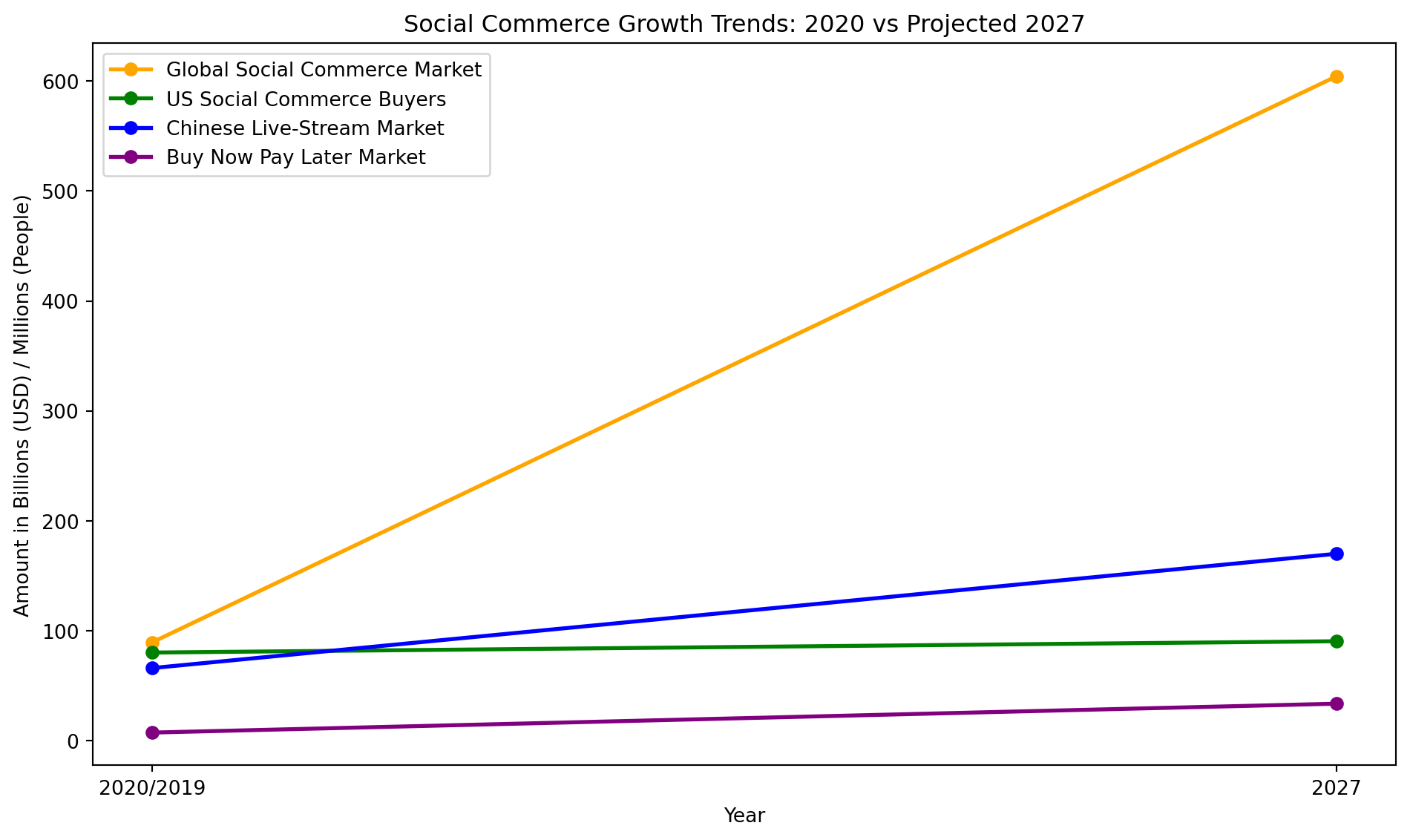

Double Eleven 11/11 celebrated on November 11 is the world’s largest shopping festival (時代財經, 2023). In June 2023, 526 million people watch e-commerce live-streams in China; online bargaining is a type of ritual (Liu et al., 2024). According to (Igini, 2024) “Asia is set to account for 50% of the world’s total online retail sales”. (The Influencer Factory, 2021) China is the furthest ahead in social shopping, the Chinese and U.S. market may be mature and growth will come from emerging markets (SEA, Latin-America).

Figure 18: Social Commerce

In the US, TikTok is the leader in social commerce (Loyst, 2024).

The Evolution of Payments: The Entry Point for Personal Finance from Mobile Wallets to Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) Services - Globally, and In Taiwan

Payments is one way consumers can take individual climate action. In the words of a Canadian investment blogger, “every dollar you spend or invest is a vote for the companies and their ethical and sustainability practices” (Fotheringham, 2017). The combination of consumption and investment is an access point to get the consumer thinking about investing. Even if the amount is small, they are a starting point for a thought process.

| Payment App | Features | Users in Taiwan | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| LINE Pay | Most popular payment app accepted all over Taiwan. Works stand-alone and inside the LINE messenger. Supports both in-store and online shopping payments, also direct P2P transfers to contacts (requires LINE Bank). Displays a map of its merchant network with discounts and coupons; integrates iPASS MONEY. | > 12 Million | Japan / Korea |

| JKOPay (街口支付) | QR code payments and P2P transfers to contacts; paying for bills. | > 7 Million | Taiwan |

| Taiwan Pay (台灣Pay) | Official Taiwanese Government app in collaboration with Taiwanese banks. Supports payments directly from bank accounts (without the need for a card). Supports QR code payments, P2P transfers to contacts and paying bills. A unique feature is cash withdrawal from ATMs without the need for a bank card. | > 6 Million | Taiwan |

| Apple Pay | Requires an Apple iOS device; uses credit/debit cards via NFC, Secure, In-app & web payments | ? | USA |

| Google Pay | Supports NFC and credit/debit cards, in-app and online payments as well as public transport. | ? | USA |

| iPASS MONEY (一卡通MONEY) | Digital version of the iPASS card which can be used for QR code payments, P2P transfers to contacts, paying bills and public transport. | ? | Taiwan |

| E.Sun Wallet (玉山Wallet) | Requires the Taiwanese E.Sun Bank and allows QR payments, P2P transfers to contacts and paying bills as well as financial management tools. | ? | Taiwan |

| Pi Wallet (Pi 拍錢包) | Payment app by the PChome online shop supporting in-store QR and online payments, and paying for bills a parking. | ? | Taiwan |

| PXPay (全聯福利中心) | Payment app by PX Mart, the largest domestic Taiwanese supermarket chain, supporting QR code payments, offering rewards and discounts and loyalty plans. Recently expanded to Korea quoting the interest of Taiwanese young people in Korean culture. In early 2025, PXPay began offering a saving and investing service called “Digital Hen” in collaboration with J.P Morgan Asset Management. According to the press release, the service aims to be a beginner-friendly financial innovation helping shoppers get into micro-investing. | ? | Taiwan |

| Hami Pay (中華電信) | Payment app by the largest phone company Chunghwa Telecom supporting NFC payments, public transport, and paying bills. | ? | Taiwan |

| Samsung Pay (悠遊卡) | Requires a Samsung device; uses NFC; integrates EasyCard and credit/debit cards; supports public transport. | ? | Korea |

Banks and fintechs both are skilled at capturing user data and digital payments are an important entry point for financial services and a source of consumer action data, shopping data. Payments is the primary way consumers use money. Is there a funnel From Payments to Investing? ESG Shopping is about Changing our relationship with money. Make commerce more transparent. Current shopping is quite superficial. One barely knows the name of the company. You don’t know much about their background. Building consumer feeling of ownership, create meaningful connections between producers and consumers.

Digitalization of payments creates lots of Point of Sale (PoS) data that’s valuable to understand what people buy. Banks have access to each person’s financial habits which makes it possible to model sustainable behavior using big data analysis. Asian markets have shown the fastest growth in the use of digital payments (McKinsey, 2020). In Macao, contactless payments are becoming the most prevalent form of value exchange, growing rapidly, up 40% from the prior year (Contactless Payments Prevalent in Macau - City’s de Facto Central Bank, 2023). In Europe, fintech is also one of the fastest-growing sectors, with 35% of the fintech ecosystem is made up by giants like Klarna, Checkout.com and Revolut and 65% belonging to newcomers; in general describe equally strong consumer uptake and friendly regulators (The European Fintechs to Watch in 2022, 2022). With the increasing number of financial services available, open banking initiatives, which set standards for financial data sharing, have the potential to improve the user experience by allowing people to access their data across all the different banking apps they use, seamlessly and securely, which improves the flow of the entire customer journey.

(Green Finance Platform, 2020) report predicts the rise of personalizing sustainable finance, because of its potential to grow customer loyalty, through improving the user experience. Similarly to good design, interacting with sustainable finance for the ‘green-minded’ demographics, providing a reliable green product is a way to build customer loyalty. The UN has been handing out Global Climate Action Awards since 2011 for idea such as the Climate Credit Card in Switzerland, which automatically tracks emissions of purchases, creates emissions’ reports for the user which can then be offset with investments in climate projects around the world (UNFCCC, 2023).

Sustainability data is an important part of the customer journey which digitalization and digital transformation make increasingly accessible. Digital receipts are one data source for tracking one’s carbon footprint. In Taiwan, O Bank makes use of Mastercard’s data to calculate each transaction’s CO2 emissions and offer Taiwanese clients “Consumer Spending Carbon Calculator” and “Low-Carbon Lifestyle Debit Card” products (Taiwan’s O-Bank Launches ’Consumer Spending Carbon Calculator,’ Rewards Carbon Reduction, 2022). This is based on technology by Mastercard, which has developed a white-label service for sustainability reports that banks can in turn offer to their clients (Mastercard, 2021). Similarly, Commons, formerly known as Joro, an independent app, analyses one’s personal financial data to estimate their CO2 footprint (Chant, 2022). ReceiptHero’s digital-receipt platform records the CO2eq footprint for each purchase, turning every transaction into a data point for tracking individual emissions, promoting eco-awareness (Digital Receipts and Customer Loyalty in One Platform ReceiptHero, n.d.). Another example is the Dutch fintech company Bunq offers payment cards for sustainability, provided by MasterCard, which connects everyday payments to green projects, such as planting trees and donations to charities within the same user interface (Bunq, 2020). However, arguably this could be considered greenwashing as Bunq only plants 1 tree per every €1,000 spend with a Bunq card. The example marketed at students cites 8 trees planted this month while students scarcely would have €8,000 to spend every month.

Sharing a similar goal to Alibaba’s Ant Forest, Bunq’s approach creates a new interaction dynamic in a familiar context (card payments), enabling customers to effortlessly contribute to sustainability. However, it lacks the level of gamification which makes Alibaba’s offering so addictive, while also not differentiating between the types of purchases the consumer makes, in terms of the level of eco-friendliness.

In Nigeria, (Emele Onu & Anthony Osae-Brown, 2022) reports how in order to promote the eNaira digital currency use, the Nigerian government limited the amount of cash that can be withdrawn from ATMs “In Nigeria’s largely informal economy, cash outside banks represents 85% of currency in circulation and almost 40 million adults are without a bank account.” [E-Naira find papers]

In Kenya, M-Pesa started since 2007 for mobile payments, used by more than 80% of farmers (Parlasca et al., 2022; Tyce, 2020). Using digital payments instead of cash enables a new class of experiences, in terms of personalization, and potentially, for sustainability. Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) is the biggest consumer payments / financing success story innovated by Klarna in Sweden in 2005 and Afterpay in Australia in 2015 but with roots in Layaway Programs created during the 1930’s US Great Depression (Kenton, 2023). By 2021, 44.1% of Gen-Z in the US had used BNPL according to (EMarketer, 2021). Users in the Gen-Z demographic mostly use BNPL to buy clothes (LHV, 2024).

People will be more likely to save and invest if it’s easy. In Sweden, point of sales (PoS) lending (BNPL, as introduced above) is a common practice, and one of the reasons for the success of Klarna, the Swedish banking startup, which has managed to lend money to more consumers than ever, through this improved user experience. Taking out loans for consumption is a questionable personal financial strategy at best. Yet, if people can loan money at the point of sales, why couldn’t there be 180 degrees opposite service - point of sales investing? And there is, called “round-up apps”. (Next Generation Customer Experience, n.d.) suggests “Targeted at millennials, Acorns is the investing app that rounds up purchases to the nearest dollar and invests the difference.” - and example of From Shopping to Investing. Likewise, many banks have started offering a service to automatically save and invest tiny amounts of money collected from shopping expenses. Every purchase one makes contributes a small percentage - usually rounded up to the nearest whole number - to one’s investment accounts. For example, (Swedbank, 2022), the leading bank in the Estonian market, offers a savings service where everyday payments made with one’s debit card are rounded up to the next Euro, and this amount is transferred to a separate savings account. Similarly, the Estonian bank (LHV, 2020) offers micro-investing and micro-savings services, with an interesting user experience innovation showing how for an average Estonian means additional savings of about 400€ per year. User experience innovation can improve accessibility and financial inclusion, while opening up a new market which used to be underserved. For example, (Y Combinator, 2023) launched a bank inside of Whatsapp for the underbanked gig workers in Latin America.

While the financial industry is highly digitized, plenty of banks are still paper-oriented, running digital and offline processes simultaneously, making them slower and less competitive, than startups. Indeed, the new baseline for customer-facing finance is set by fintech, taking cues from the successful mobile apps in a variety of sectors, foregoing physical offices, and focusing on offering the best possible online experience for a specific financial service, such as payments.

Traditional banks and fintechs are becoming more similar than ever. 39% of Millennials are willing to leave their bank for a better fintech (n = 4282); innovation in payments helps retention (PYMNTS, 2023). The European Central Bank describes fintech as improving the user experience across the board, making interactions more convenient, user-friendly, cheaper, and faster. “Fintech has had a more pronounced impact in the payments market […] where the incumbents have accumulated the most glaring shortcomings, often resulting in inefficient and overpriced products,” Yves Mersch, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB says in (European Central Bank, 2019).

There are also people who are concerned with digital payments. There are concerns digital currencies also help to “democratize financial surveillance”. China was a money innovator introducing paper money in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) (First Paper Money, n.d.). Jeff Benson (2022) is troubled by the “use the e-CNY network to increase financial surveillance” (Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) Tracker, 2023) believes digital currencies make tracking easier. Economist Eswar Prasad argues that the era of “private” cryptocurrencies is coming to an end down as they’ll be supplanted by government-backed central bank-issued digital currencies that marry blockchain’s efficiency with legal oversight (MARISA ADÁN GIL, 2022). The same author compares WeChat, Alipay vs the digital yuan (Yahoo Finance, 2022).

There are many neobanks, or challenger banks, far too many to list. The table only includes a small sample of banks and the landscape is even larger if one includes the wider array of fintechs. Neo-banks often use sustainability marketing. Legendary investor Warren Buffett’s company Berkshire Hathaway invested $1 Billion USD in Nubank, Brazilian digital challenger Bank, while reducing its stakes in Mastercard and Visa, signaling growing faith in digital banking platforms over traditional card-issuers (Andrés Engler, 2022).

The following popular (totaling millions of users) robo-advisory apps combine sustainability, personalization, ethics, and investing however, they are mostly only available on the U.S. market.

| Service | Features | Availability |

| Goodments | Matching investment vehicles to user’s environmental, social, ethical values | USA |

| Wealthsimple | AI-assisted saving & investing for Millennials | USA, UK |

| Ellevest | AI-assisted robo-advisory focused on female investors and women-led business | USA |

| Betterment | AI-assisted cash management, savings, retirement, and investing | USA |

| Earthfolio | AI-assisted socially responsible investing | USA |

| Acorns | AI-assisted micro-investing | USA |

| Trine | Loans to eco-projects | USA |

| Single.Earth | Nature-back cryptocurrency | Global |

| Grünfin | Invest in funds | EU |

| M1 Finance | Finance Super App | US |

| Finimize | Investment research for anyone | US |

| NerdWallet | Financial clarity all in one place | US |

| Tomorrow Bank | Green Banking | EU |

| Marcus Invest | Robo-Advisor | US |

| Chipper | Digital cash app for African markets | Africa |

| Lightyear | Simple UI for Stocks, ETFs, interest from Estonia | EU |

| Ziglu | UK simple investing app | UK |

| Selma | Finnish investing app | EU |

| Monzo | Bank | UK |

| Nubank | Bank | Brazil |

| EToro | Investing and copy-investing | EU |

| Revolut | From payments to investing | UK, EU |

| Mos | Banking for students | US |

| Robinhood | Investing | US |

| Mintos | Buy bonds and loans | EU |

Becoming a major payments player requires navigating the maze of global directives, including legislation regarding finance, privacy, data protection, money laundering, localized licensing regimes, and more. For an example, Google Wallet’s privacy notice sheds some light on how a unified payments profile links services under one’s Google account while following its broader data‑use policies (Google, 2025).

Alipay is by far the largest payments super-app and provides two investment services within it’s payments platform, first launching Yu’e Bao (餘額寶) in 2013, which automatically invests small amounts on the users’ accounts for returns typically above those of traditional banks’ saving accounts, and later in 2015 Ant Fortune (螞蟻財富), offering access to thousands of investment products from partner companies (KraneShares, 2020). Alibaba owns over 30% of Alipay and both companies are pushing for increased use of AI within their services (“Chinese Billionaire Jack Ma Sees AI Future for Ant Group, in Rare Appearance,” 2024).

Similarly, both Line, through it’s Line Pay, Line Securities, and Line Bank, and Naver, though Naver Pay, have been on a path for several years evolving into comprehensive financial platforms (Anna J. Park, 2023; LINE Corporation, 2019). None of these payment apps have a specific focus on sustainability while Alipay does have a separate sustainability-focused service called Ant Forest for planting trees. Payment apps created by Apple and Google are less-feature rich focusing on payments only, and are being challenged by newcomers. An Australian fintech Douugh released it’s robo-advisor in 2024 (Paul, 2024). Douugh’s tagline explain the ethos of a unified financial app simply: “One app to spend and grow your money”. The newest generation of robo-advisors are integrating large-language modules, for example Reuters highlights the Chinese brokerage firm Tiger Brokers as one among 20 Chinese companies integrating DeepSeek deeply into asset management from simple chat functionality all the way to executing trades.

Established Consumer Payment Giants

| Service | Features | Users | Investing | Savings | Shopping (Payments) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alipay | Payments, banking, Yu’e Bao, Ant Fortune investing | 1.3 billion | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| WeChat Pay | Payments, financial services, Licaitong investing | 900 million | Yes | No | Yes |

| Apple Pay | Contactless payments | 744 million | No | No | Yes |

| PhonePe | Payments, mutual funds, digital gold | 590 million | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Paytm | Payments, banking, Paytm Money for stock & fund investing | 350 million | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Google Pay | Payments, loyalty, transit | 150 million | No | No | Yes |

| Samsung Pay | Mobile payments | ? | No | No | Yes |

| Zelle | Bank-to-bank P2P payments | ? | No | Yes | Yes |

| Nubank | Full features of a traditional bank in a digital form | ? | No | Yes | Yes |

Growth Companies

For human psychology, the fact that money on a Wise account will accrue value while on Monese it’s just static, immediately makes Wise more attractive, even if the amounts are small.

| Service | Features | Availability | User Base | Investing | Savings | Shopping (Payments) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venmo | P2P payments, crypto investing | USA | 70 million | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cash App | P2P payments, stock & Bitcoin investing | USA, UK | 57 million | Yes | No | Yes |

| Chime | Online banking services including spending accounts, savings accounts | USA | 22 million | No | Yes | Yes |

| MoneyLion | Banking, investing, credit-building loans, financial tracking tools | USA | 20 million | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| NerdWallet | Financial clarity all in one place | USA | 19 million | No | No | Yes |

| SoFi | Loans, banking, robo-investing, stock & crypto | USA | 10 million | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Albert | Budgeting, saving, spending, investing, access to financial advisors | USA | 10 million | Yes | Yes | No |

| Acorns | AI-assisted micro-investing | USA | 5.7 million | Yes | No | No |

| Wealthsimple | AI-assisted saving & investing for Millennials | Canada, USA, UK | 2.6 million | Yes | Yes | No |

| Qapital | Saving and investing with gamification features | USA | 2 million | Yes | Yes | No |

| M1 Finance | Finance Super App | USA | 1 million | Yes | No | No |

| Finimize | Investment research for anyone | Global | 1 million | Yes | No | No |

| Robinhood | Investing | US | ? | Yes | No | No |

| Betterment | AI-assisted cash management, savings, retirement, and investing | USA | ? | Yes | Yes | No |

| Revolut | From payments to investing | UK, EU | ? | Yes | No | TRUE |

| Monzo | Bank | UK | ? | No | Yes | No |

| eToro | Investing and copy-investing | EU | ? | Yes | No | No |

| Marcus Invest | Robo-Advisor | USA | ? | Yes | No | No |

| Varo Bank | Online banking services including checking and high-yield savings | USA | ? | No | Yes | Yes |

| Stash | Micro-investing platform enabling small investments | USA | ? | Yes | No | No |

| Mint (Ceased operations) | Budgeting tools, bill tracking, free credit score monitoring | USA | ? | No | No | No |

Up-and-Coming Startups

| Service | Features | Availability | User Base | Investing | Savings | Shopping (Payments) | Sustainability Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chipper Cash | Digital cash app for African markets | Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, USA | ? | No | No | Yes | No |

| Douugh (Merged with Goodments) | AI financial wellness app, smart account, saving tools | USA, Australia | ? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| DUB | Copy-trading, mirror trades of notable figures | USA | 1 million downloads | Yes | No | No | No |

| Earthfolio | AI-assisted socially responsible investing | USA | ? | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Ellevest | AI-assisted robo-advisory focused on female investors and women-led business | USA | ? | Yes | No | No | No |

| Goodments (Merged with Douugh) | Matching investment vehicles to user’s environmental, social, ethical values | USA | ? | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Grünfin (Ceased operations) | Invest in funds | EU | ? | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Lightyear | Simple UI for Stocks, ETFs, interest from Estonia | EU | ? | Yes | No | No | No |

| Mintos | Buy bonds and loans | EU | ? | Yes | No | No | No |

| Mos | Banking for students | US | ? | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Selma | Finnish investing app | EU | ? | Yes | No | No | No |

| Single.Earth | Nature-backed cryptocurrency | Global | ? | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Tomorrow Bank | Green Banking | EU | 120,000 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Trine | Loans to eco-projects | USA | ? | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Ziglu | UK simple investing app | UK | ? | Yes | No | No | No |

Considering AI assistant for ESG investing, (G. K. S. Tan, 2020) proposes “financial ecologies” to understand the dynamic relationships between various actors: investors, advisors, government, where the government plays an active role in growing financial inclusion and responsible financial management; however, the paper further suggests that current robo-advisors (available in Singapore) make the investor captive to the agency of AI, making the person lose agency over their financial decisions.

The Psychology Saving: Anthropomorphism and Loyalty Schemes

There are at least two ways to look at sustainable savings, however related. In general, people will save nature if it also saves money. This section looks at savings in the financial sense of the word. Savings in the sense of CO2e emission and environmental cost reductions have an entire separate chapter dedicated to them titled ‘sustainability’ however a short definition might be valuable here as well.

Environmental Savings means “the credit incurred by a community that invests in environmental protection now instead of paying more for corrective action in the future” (see Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy, 2018) and (Yale, Princeton, Stanford, MIT and Vanderbilt Students Take Legal Action to Try to Force Fossil Fuel Divestment - The Washington Post, n.d., p. 33).

Savings in CO2e equivalent emissions: CO2e savings are the amount of CO2e reduction one manages to achieve by changing one’s behavior and influencing others (people, companies). While the individual footprint is so small, the largest reduction will come from influencing large groups of people, either by leadership, role-model, or other means.

In theory, ethical savings accounts only finance businesses aligned with the customers’ values: screening out problematic and potentially harmful industries such as fossil fuels, tobacco, weapons, etc.; in practice, one should carefully evaluate a bank’s investment principles, environmental policies and governance practices (Ethical Savings, 2023).